On May 5-8, 1945, an uprising against the German occupation forces took place in Prague. The result was the peaceful surrender of the Germans to the American, which prevented mass bloodshed on both sides. The uprising was commanded by General Karel Kutlvašr, whose wife, Jelizaveta, recalled in 1968: “In the evening, it must have been May 3, my husband came very late from somewhere and told me solemnly, as he knew how, terribly calmly and modestly: “I have been given a great honor, I have been entrusted with military command if Prague needs defense.”

It Started at Sechs O’clock in the Morning

“It’s sechs o’clock.”

This sentence, which contained only one German word, was broadcast by announcer Zdeněk Mančal on the morning of May 5, 1945. Czech Radio thus let the inhabitants of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia know that something was happening. People listening to the radio understood the spontaneous impulse to rise and began tearing down German signs in the streets.

That was the beginning, but it wasn’t easy. We are talking about a time when radio was completely dominant in the dissemination of information. Czechoslovak television only began broadcasting in 1953 and printed newspapers were published once a day. They could not be compared to the radio’s ability to react immediately. Therefore, whoever had the radio in their hands controlled the situation.

Therefore, on Friday, May 4, the Germans occupied all technical workplaces, and they deployed heavy machine guns and wire barriers near the radio building. The SS guards ordered all employees to leave the building in the evening. Of the announcers, only Zdeněk Mančal remained on the radio overnight, who was supposed to start broadcasting on the morning of May 5.

Before noon on May 5, the German intendant (head of the Bohemia and Moravia radio group of the Reich Radio), Ferdinand Thürmer, called another 70 fully armed SS soldiers directly into the building. Still, they were unable to find their way around the building. This was because Czech employees had been tearing down German signs since morning, so the summoned military reinforcements were disoriented and could not find the rooms where the broadcast was being made. At noon, the Czechoslovak and American flags were hoisted on the building, while the planned hoisting of the British and Soviet flags was prevented by gunfire.

On the contrary, the Czech police had an advantage over the Germans. The day before, they had come to the radio building. Officially, they were to speak on the program Beware of Pickpockets. In reality, however, the radio resistance fighters were showing them the location of the radio studios and teaching them how to navigate the complex labyrinth of radio corridors. At exactly 12:32, they managed to re-enter the building. The fight for the radio station had begun.

The SS garrison commander was surprised by what was happening in the radio station. Although he had occupied the main entrances to the building, the main staircase and the corridors, the Czech fighters entered the radio station through the roof, through the walls of the neighboring houses, along ropes, ladders and even through holes knocked out in the outer wall of the neighboring undeveloped plot.

The police, with the help of Czech employees, took control of the broadcasting and technical workplaces. The announcers barricaded themselves in the broadcasting room. At 12:33 p.m., the first radio call for help was made: “We are calling the Czech police, the Czech gendarmerie, and the government army to help Czech Radio. Come to our aid immediately. We are calling all Czechs.”

An authentic recording of Czech Radio’s call for help:

General Karel Kutlvašr later recalled this moment as a turning point: “This radio call, this call for help was the magic word that electrified the masses of the Prague people and the entire Czech nation to rise against the occupiers. (…) It was something natural, like a sudden storm or whirlwind, like a great flood, or a strong and violent fire. At that moment, the decision of so many people to go out into the streets and with their bare hands, teeth, and feet, in short, with everything possible, to join the fight. Into the fight.”

The Uprising

On the morning of May 5, Karel Kutlvašr returned home from a conspiracy meeting. He found his wife in the euphoria that had reigned in Prague since the morning radio report. The couple even argued because the wife wanted to hang the Czechoslovak flag from the window, and the general did not want to draw attention to himself, the commander of the uprising. They talked about it for half an hour before the wife jumped to the window and hung the flag. Her husband emotionally realized that it was the flag he had saved in his last military post before the war, when he commanded a division in Hradec Králové, and had hidden it throughout the war. And because the times were set for change, the windows in the surrounding houses immediately began to open, and soon flags were flying from the windows of the entire street.

In the afternoon, the Czech National Council called on citizens to build barricades. (The Czech National Council was an illegal organization that oversaw the domestic resistance. The later, unrelated Czech National Council was the legislative body of the Czech Socialist Republic and later the Czech Republic from 1969 to the end of 1992. This “Czech Parliament” became the highest body of state power of the independent Czech Republic after the division of Czechoslovakia.)

People built all night, in heavy rain and complete darkness. (Across the entire Protectorate, since August 1939, it had been ordered that windows be completely covered from dusk to dawn so that illuminated cities would not serve as landmarks for aircraft. Even street lamps were not lit, the cities were plunged into darkness.) Hundreds of thousands of Prague residents took part in building the barricades. They built 1,600 of them that night.

The fighting in the streets of the city lasted until May 8. The Germans deployed aircraft, tanks, and artillery. They made a tactical mistake by not occupying all the bridges, so when they finally attacked Hlávka Bridge, German tanks drove Czech men, women, and even children ahead of them to clear the barricades for them. They thus regained the island of Štvanice, but when the Czech side threatened them that if they continued this barbaric method of fighting, German women would be used as human shields on the barricades, the Germans withdrew. In the four days of the uprising, a total of 2,898 people, including soldiers, died in the fighting. The retreating, stressed-out Germans massacred many civilians.

Many people joined the fighting spontaneously, but the military command already controlled most of the action, including the events on the barricades. But the people who survived the Gestapo raids and were actually working secretly for the resistance during the war. The Germans were therefore surprised that there was still anyone left to resist them after the end of the war. Karl Hermann Frank, commander of the police and SS units in the Protectorate, later said in court: “We were surprised that the Czechoslovak army did not disappear.”

Karl Hermann Frank

The German State Minister for the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was nicknamed “Bloody Dog Frank”. After the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, he ordered the extermination of the villages of Lidice and Ležáky, sending thousands of people to concentration camps. He handed out death sentences like they were candy; he signed the last one on May 1, 1945. His motto was “Whoever is not with us is against us. And whoever is against us will be crushed.”

But on May 6, a very important meeting took place in the Czernin Palace. (The palace is now the seat of the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs. During World War II, the Office of the Reich Protector Konstantin von Neurath and, later, Reinhard Heydrich was located here. State Secretary K. H. Frank also had an office here.)

Frank met with a three-member delegation, which also included Karel Kutlvašr. He recalled: “At the entrance to K. H. Frank’s office, he greeted us at the door without raising his hand or saying Heil Hitler, I think he greeted us with a civil Guten Tag.”

Before the negotiations even began, Frank asked: “Is it true that Lieutenant Toussaint is captured, and is he alive?” After receiving a positive answer, he stood up and, in front of the Czech negotiators, telephoned his father, who already thought his son was dead. That father was General Rudolph Toussaint, the Wehrmacht commander in Prague…

The demands of the Czech side were precise: the transfer of all sovereignty over the territory of Bohemia and Moravia into the hands of the Czech National Council, the transfer of all administrative affairs into the hands of Czech authorities, and the transfer of railways and all transport into Czech hands…

Frank had a big problem with the handover of the railways and did not promise it: “A fighting army must have its back and transport secured, without that it cannot fight! Marshal Schörner is determined to fight to the end.” Then he added words about Germany’s fight for Europe, for which young Germans are fighting and sacrificing themselves.

The situation developed quite quickly at that time. So, just three days later, KHF and his family escaped from Prague. While escaping near Rokycany, just outside Pilsen, American soldiers captured him and handed him over to the Czech justice system. He was sentenced to death and executed on May 22, 1946. His last wish was: salami with eggs, a glass of brandy, a last cigarette, and not to be led to the gallows in handcuffs. All of these wishes were fulfilled. Six thousand people came to watch the execution, who saw the pale Frank, in whose eyes you could see fear. The executioner and his assistants were dressed in black SS uniforms. This was very strange, but it corresponds to the spirit of the times and the fact that K. H. Frank was famous for his cruelty towards the Czechs, when his ultimate goal was the extermination of the Czech nation.

Karl Hermann Frank, in 1938, sitting next to Adolf Hitler, and seven years later, seconds before death.

A Gentleman’s Surrender and then Common Imprisonment

The German garrison in Prague numbered 30,000 heavily armed Germans; other units could have rushed to their aid from the Prague area. German war documents showed what they planned to do with Prague at the end of the war – to defend on the left bank of the Vltava, and to destroy the city on the right. However, this was prevented by the rapid progress of the Prague Uprising. Over time, the Germans became aware that their situation was hopeless, and they wanted to be captured by the American, not the Soviet, army at all costs.

The day after the meeting with K.H. Frank, on May 7, General Kutlvašr interpreted an urgent message to Franz Friedrich Rudl (Rudl was one of K.H. Frank’s closest advisors and, during the uprising, also the mediator of the International Red Cross between the two sides): “The Czech National Council orders that General Toussaint appear tomorrow, May 8, at 10 a.m. at the headquarters of the Czech National Council in order to accept the terms of unconditional surrender.”

German General Rudolph Toussaint, commander of the Wehrmacht in Prague, arrived the next day, at 10:45 a.m. General Kutlvašr began the main part of the meeting with the words: “Wir haben keine Zeit zu verlieren.” (We have no time to waste.)

General Toussaint knew that the situation was critical. The day before, he had rejected the request of the aforementioned Field Marshal Ferdinand Schörner, whose army of several thousand men was one of the last viable parts of the German armed forces, to have Prague bombed so that German troops could pass through it and be captured by the Americans.

Therefore, he was willing to negotiate surrender; in exchange for the free transit of Wehrmacht units through the city into Allied captivity. General Kutlvašr recalled: “When the treaty was signed, Toussaint burst into tears and said: ‘I am personally completely destroyed, I have lost everything. My homeland, my family, and everything else.’ Otherwise, he behaved militarily and with dignity.” After the treaty was signed, a tall young prisoner with a bandaged head was brought to Rudolph Toussaint – his son. General Kutlvašr then allowed his opponent to take his son with him.

Rudolph Toussaint was eventually sentenced to life imprisonment and was finally released in 1961. He served his sentence in prisons in Leopoldov and Pilsen in Bory, where a special encounter occurred years later. Karel Kutlvašr, who was sent to prison by the communists after the putch in 1948, was also imprisoned there for some time. The young prisoner Antonín Souček, who was a political prisoner for illegally crossing the western border, had an idea: this is what they should say to each other. The two men spent three days together, debating and playing chess. Rudolph Toussaint told Karel Kutlvašr that he respected him, that he was a true soldier in his eyes, and that it was an honor for him to surrender the German troops in Prague to him.

We Liberated Prague Ourselves

The Czechs liberated Prague themselves at the end of the war – this is a simple truth that was not allowed to be spoken for over forty years. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill wanted Prague to be liberated by the Americans because he wanted to prevent Czechoslovakia from falling into the Soviet sphere of influence after the war. Unfortunately, he was not listened to, so the Americans under the command of General Patton liberated only western Bohemia and remained standing on the demarcation line Karlovy Vary – Pilsen – České Budějovice, agreed upon by General Eisenhower and Stalin. The Americans waited near Pilsen, 100 km from Prague, and the Russians were making a difficult return to Prague through the Ore Mountains from defeated Berlin.

On May 6, a German Messerschmitt 262 bomber dropped a 500-pound bomb on the radio building. The building collapsed into the hall, where it exploded. There are dead on the spot, and the equipment is completely damaged. Despite this, the broadcast was interrupted for only 90 minutes, when a makeshift broadcast began from Strašnice (near the tram barricade in one of the pictures) and later from the church in Vinohrady.

Therefore, the Red Army arrived in the city only when the insurgents had the metropolis effectively in their hands. Soviet units were engaged only in a few isolated skirmishes with the rearguard of the retreating Germans, or they fought with lone insidious shooters who did not want to acknowledge the surrender.

And although the communist regime had convinced the Czechs until the Velvet Revolution in November 1989 that the Red Army had saved them in 1945 and that they should be grateful for that, the opposite is true. The Prague Uprising and the subsequent surrender of the Germans in Prague and their departure to the West hastened the defeat of the Nazi troops and thus saved the lives of Soviet soldiers.

This Will Not Go Unpunished

When Karel Kutlvašr signed the agreement on the surrender of the German garrison in Prague, according to eyewitnesses, he said at the time that it would not go without retribution. And he was right. Not only because we’d saved Prague ourselves. And regardless of the fact that if Karel Kutlvašr had not signed the agreement of the surrender of the Wehrmacht and its passage through the metropolis with Toussaint, the Germans would have fought their way out of the city with their heavy weapons, leaving thousands dead behind them.

Kutlvašr stole the liberation of Prague from the Soviets. After the communist putch in February 1948, a list of twenty generals who were dismissed from the army was compiled within hours, Karel Kutlvašr among them. His wife Jelizaveta wrote in July 1948: “Every day brings only bad and sinister news. The death of Jan Masaryk, the abdication of President Beneš, the elections that almost erased every honest person from the world, new presidential elections, and undignified comedies around it. Many people are going into exile. The standard of the state and of every individual is falling lower and lower. Where are we going? Whistleblowing and crooked characters are looking at us from all sides.”

The new totalitarian regime proceeded in such a way as to dominate and intimidate the nation. So it killed, expelled or broke the rebellious people and made the rest of the population the so-called silent majority. A dark staged trial period followed, when many politically inconvenient people were severely punished. By confiscation of property, forced eviction, imprisonment, forced labor in uranium mines and also death. Among these hundreds of thousands of punished people were political opponents of the totalitarian regime, members of the army of the former democratic state, of course, Czechoslovak RAF pilots who fought for their homeland at the front. Also, members of the resistance and, of course, hundreds and thousands of clergy.

Karel Kutlvašr was accused of high treason and in a fictitious trial was demoted to private on May 16, 1949 and sentenced to life imprisonment. Jelizaveta Kutlvašrová recalled the announcement of the verdict in an interview with researcher Roman Cílek: “It was a terrible day. Everything dragged on strangely; we were thrown out of the courtroom several times – they said they had to check to see if there were any bombs. Unbearable tension. Finally, the presiding judge read the verdict against thirteen or fourteen defendants. I thought I would faint with joy when I heard that Karlíček had been sentenced to life imprisonment. Only life imprisonment! Right next to me, however, Mrs. Bacílková and Mrs. Kovaříčková, whose sons had been sentenced to death, screamed in horror. Imagine, young boys, university students! As a childless woman, I can hardly imagine the feelings of those mothers, but that horrible memory will always torment me.”

Years later, Josef Slanina, who was sentenced to fifteen years in prison in the same fabricated trial, spoke about the exceptional strength of Karel Kutlvašr’s character: “They took us out of the large court room in Pankrác to a closely adjacent gloomy and poorly lit corridor. We stood there and the guards were about to take us to prison through the catacombs, which evoked feelings of long-ago times. The mood was gloomyon. D’t be surprised: three gallows, one life sentence and long sentences for each of us. We were mistreated, beaten, nervous, we had no illusions that we could survive such an endless period of life in prison. General Kutlvašr, who they’d hatefully determined in the verdict that he should never leave prison again, felt what was in the air and showed himself as a soldier, as a man who knows how to impose his will on others at the right moment. Suddenly, into the almost funereal silence, he commanded: “For the last time, on my command… Attention! Forward march!” We obeyed and on the way through those ghostly underground corridors we marched as if on a parade, some of us even started to sing, then literally shout a marching song about the strength of a lion and the heart of a falcon. It was bouncing off the walls and it must have been such a powerful moment that not one of the guards dared to scold us in any way.”

(The aforementioned song has been the anthem of the Czech Sokol since 1882. It had been banned during the Nazi occupation, but during the Prague Uprising, it was repeatedly played by Czech Radio, thus strengthening the determination of the inhabitants of Prague to resist the German occupiers. In the last verse of the second stanza, the following is sung: The sacred motto of the Sokol: “For the nation, dear homeland!”)

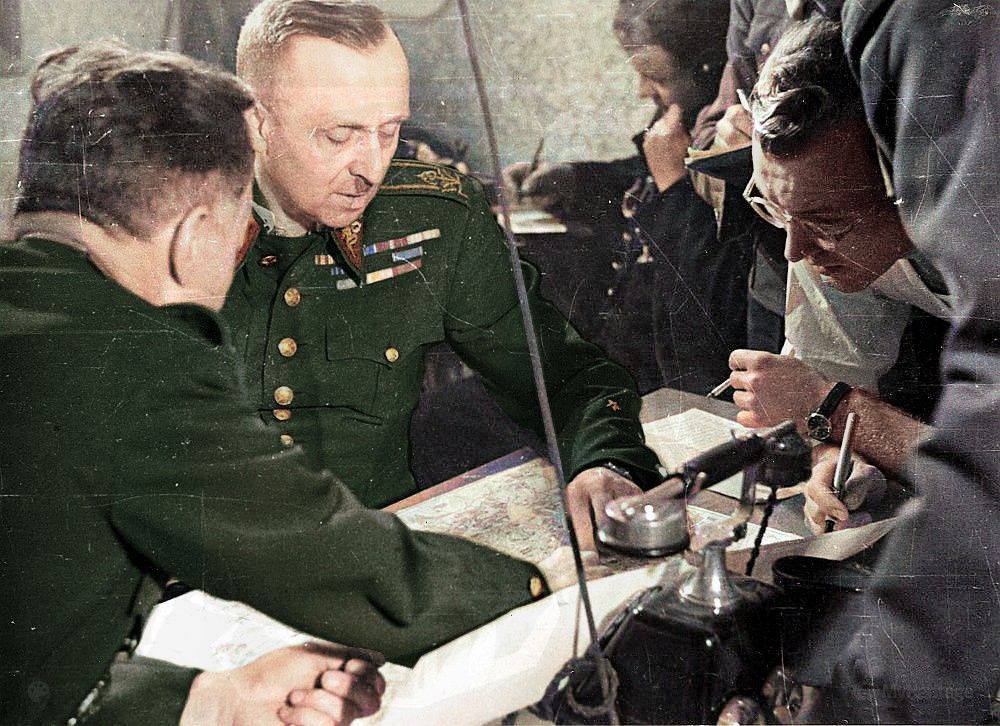

General Kutlvašr in the headquarters of the Prague Uprising, after the war with President Beneš (seated first from the left), and after less than two years in prison

The Totalitarian Regime Punishes Consistently

The regime also took revenge on Jelizaveta Kutlvašrová. She had to move several times to increasingly worse conditions. They didn’t want to employ her anywhere because everyone knew whose wife she was. When she got a job, she was soon fired again. (Let’s just remind you that the socialist state had artificial employment. There was a work obligation. Everyone had to work and anyone who didn’t work was committing the crime of parasitism.) Jelizaveta Kutlvašrová packed candies in a chocolate factory, worked in a porcelain warehouse, collected construction waste. She learned to work with a milling machine, a drill and a lathe, was a seamstress and an umbrella repairman.

Part of her husband’s punishment was the confiscation of his property. So, in addition to Jelizaveta having to move to increasingly worse and more appalling apartments, the state confiscated her furniture and put it up for public auction. The family tried to buy back at least some of her property. Kutlvašr’s brother-in-law, František Tichý, bought back some of the furniture using money from the family. Jelizaveta got some of the furniture back, but František was then convicted and sent to a labor camp for it.

Zdeněk Mančal did not escape a completely incomprehensible punishment either. The man whose voice started the Prague Uprising was very popular after the end of the war. He was invited to lectures and discussions, where he told the truth about how the Prague Uprising took place. However, because the truth was different from what the communists said about this time, Zdeněk Mančal was arrested in May 1949 and later charged with high treason. He was sentenced to five years, serving three of which he spent working in uranium mines. After his release, he was only allowed to work in blue-collar professions. He died in 1975, at the age of just 62.

We Will Not Forget

Karel Kutlvašr was released from prison after eleven years, after an amnesty by President Antonín Novotný. Although he was already of retirement age, he had to start working because he was initially not granted any pension. Later, as an enemy of the regime, his pension was only 230 crowns (the average pension at the time was roughly four times that). First, he became a security guard in the Prague Castle Riding School gallery. However, visitors there recognized and talked to him, and the regime did not like that. Therefore, he became a night porter at the brewery in Nusle.

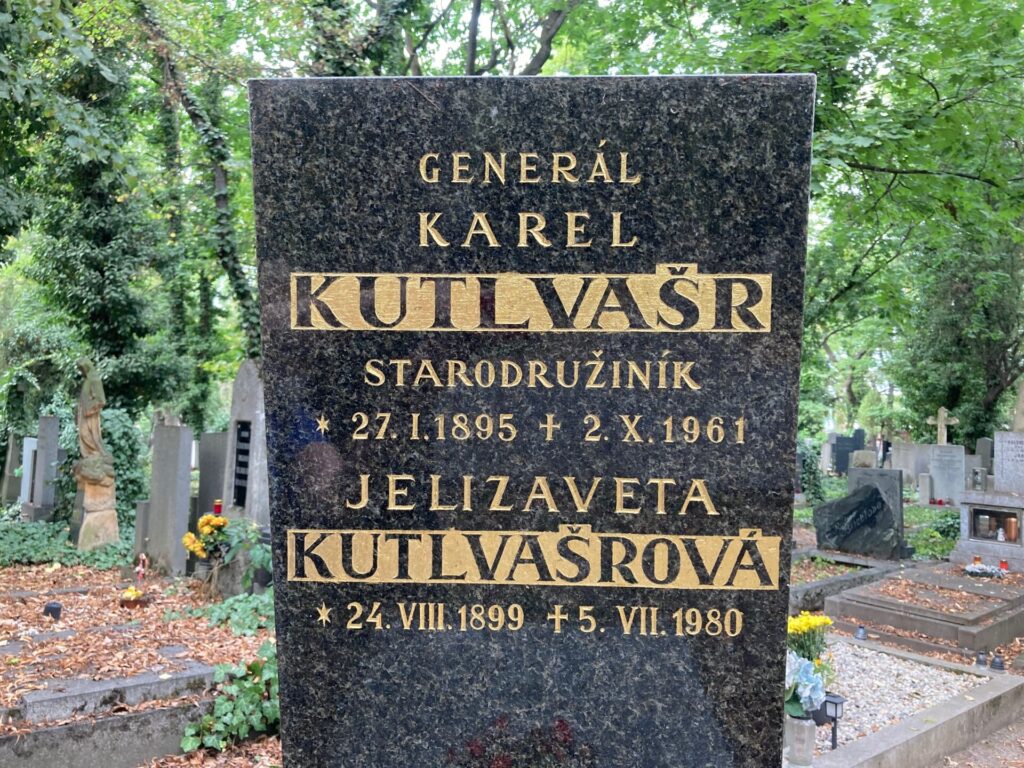

Eleven years in prison naturally took its toll on his health. Among other things, he suffered two heart attacks there. On October 2, 1961, he went to the doctor for a check-up and died of a third heart attack right in the doctor’s office.

Motto on the tombstone of the Kutlvašr couple at the Olšany cemeteries:Dieu – Patrie – Noblesse. God – Fatherland – Nobility. (His other credo was: To endure, never to give up.)

The following sentence also testifies to Karel Kutlvašr’s attitude to life: “I did my military duty, honestly and conscientiously, that’s what matters to me, just this recognition. I consider the rest to be secondary.”

Jelizaveta Kutlvašrová: “At the door of the doctor’s office, my husband staggered and fell into the hands of the assistant walking behind him. Before they could do anything, he had died. A heart attack. It was his third, two in prison, but he hadn’t told me about them so I wouldn’t worry. And without suspecting it, he died in the arms of a man whose father had been my husband’s adjutant in the 1st Regiment in the Russian Legions. That doctor’s name was Vladimír Endt. And his father, František, was a witness to our acquaintance in Kansk, Siberia, in 1919.”

Thanks to his wife’s initiative, Karel Kutlvašr was fully rehabilitated in 1968. After 1989, he was posthumously promoted to army general, and in 2017 he was awarded the highest Czech order, the Order of the White Lion.

The Nusle Brewery has been brewing beer since 1757 (some sources mention the brewery’s founding in 1694). Its importance grew until it was the largest industrial brewery in Central Europe. The brewery was closed in 1960. Wine was then processed there, and then there was the Nuselská beer garden restaurant. Then the area fell into disrepair, until in recent years a new development project with apartments and commercial premises has been built up here. And its architects, the developer and local politicians, also thought about the memory of General Kutlvašr.

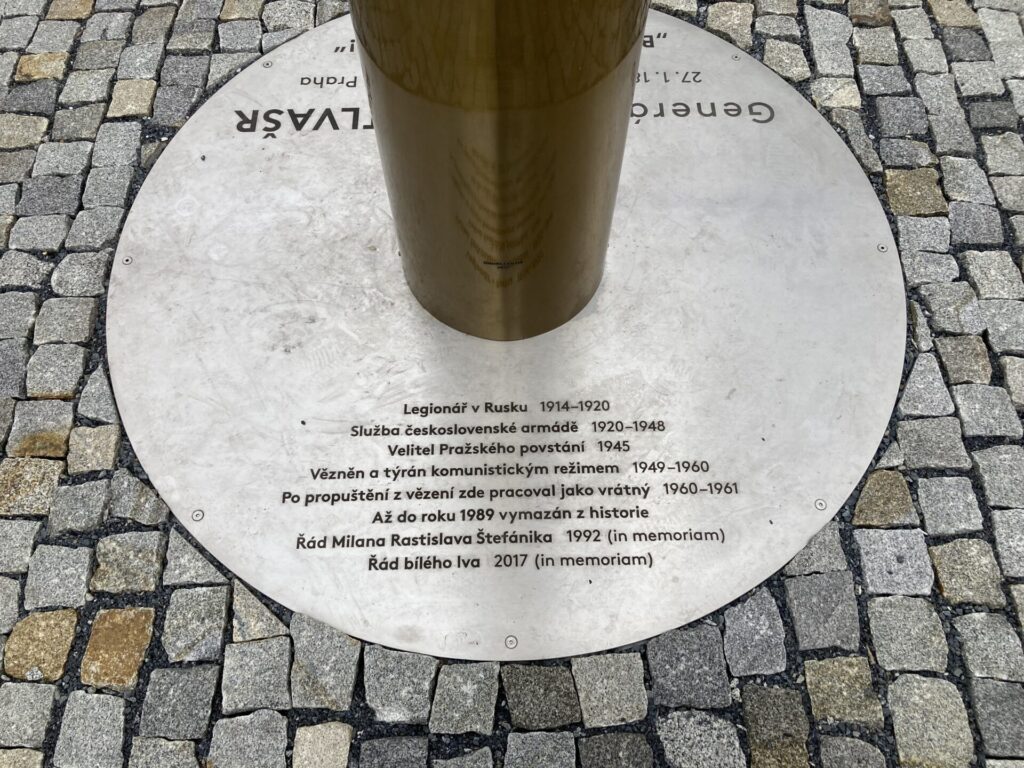

In the area there is a sculpture titled “General Kutlvašr’s Battalion,” complete with a water fountain. At night, the sculpture is illuminated to commemorate the night shifts that the general served in the brewery. At the foot of the sculpture is a sentence that Karel Kutlvašr said to his colleague in 1939, when he was asked if he was sure that no one would betray him.

The sentence reflects the character of a soldier and a convinced patriot: “Nothing is accomplished without risk.”

Quotes:

The memoirs of Karel Kutlvašr are from the book by Pavel Švec, KK’s great-great-nephew: General Karel Kutlvašr – memories of the Prague Uprising

Roman Cílek: Three gallows, on one of them a villain

Roman Cílek: Woe to him who stands out from the crowd

Not far from the Nusle Brewery, there is a bust of Karel Kutlvašr on the local town hall. The adjacent park is named Karel Kutlvašr Square.