The sentence in the headline is a quote from Sir Nicholas Winton, who, just before the war, saved the lives of 669 children, mostly from Jewish families. He is rightly called the “British Schindler”, yet no one knew his noble act until 1988. That is, for 50 years…

Documents about the rescue of hundreds of children were discovered by Winton’s wife, Greta, in the attic of their house. She handed them over to historian Elizabeth Maxwell, founder of the journal Holocaust and Genocide Studies. She was also the wife of Robert Maxwell, a British media magnate with partly Czechoslovak roots. Maxwell was a soldier in the British army who took part in the landings in Normandy and was awarded the British Military Cross, but was also a descendant of a poor Jewish family, a significant part of which was murdered in the concentration camp in Auschwitz.

Elizabeth Maxwell then organized a meeting of Nicholas Winton with “his children” in the BBC studio on Esther Rantzen’s That’s Life program.

“Could You Stand Up, Please?”

Věra Gissing, née Diamantová, one of Winton’s “children”, recalled this in 2009 (she was rescued together with her sister, Eva; their parents perished in a concentration camp during the war). In 1988, Esther Rantzen, whom she knew, called her and invited her to the studio.

Twenty seconds into the video, Věra learns that she is sitting next to the man who saved her life. As she says in the Czech TV video, she did not know who organized the whole event until then: “You can imagine what it must have meant for our parents, who were dying, but could say to themselves: Thank God, the children are safe. That is priceless.”

On the broadcast of That’s Life the following Sunday, more of the children rescued by Nicholas Winton were in the audience (the video is a shot from time 0:48). Many of them were contacted by Věra Gissing, who was skilled in organization and had lists of children from “Czech” schools at home even after all these decades.

Now seated to the right (from the camera’s point of view) of Nicholas Winton is his wife Greta and Věra Gissing is next to him on the left. Esther Rantzen then asks: “Can I ask if there is anyone in our audience tonight who owes their life to Nicholas Winton? If so, could you stand up, please?” Almost forty people stand up in the audience. Nicholas Winton stands up, turns to them, then sits down, exchanges a loving sight with his wife, and rubs his eyes with emotion.

The Munich Betrayal

To understand the context, it is necessary to go back to September 1938, when the Munich Agreement was signed. This agreement ceded a significant part of the border territory of Czechoslovakia to Hitler’s Germany. It was the so-called Sudetenland, where most of the population was of German nationality.

The agreement was signed by Adolf Hitler (Germany), Benito Mussolini (Italy), Neville Chamberlain (Great Britain) and Édouard Daladier (France). Representatives of Czechoslovakia were present at the meeting but were not allowed to interfere. (Why is that? Well, that would be beyond the scope of this blog. Czech and German history are deeply interwoven with Germans having lived in the territory of today’s Czech Republic for many centuries; mutual relations only started to become fundamentally complicated at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.)

Therefore, the representatives of the four countries made the decision about our territory, which is why this agreement is often referred to by Czechs as the “The Munich Betrayal” or “About Us Without Us” in Czech. The motivation of the representatives of Great Britain and France was the belief that if they complied with Hitler’s territorial claims, they would avert the danger of a world war – how false this assumption was. It became clear in less than a year.

The Czech inhabitants of the Sudetenland were evicted inland. If they wanted to stay, they were subjected to discrimination, and they became second-class citizens in their homes. So there was an exodus – people took only the most necessary things and furniture and moved either to relatives or tried to find a home in another way. Many of them lived in refugee camps, not unlike those we know from many unstable parts of the world today.

We Can’t Let These People Down

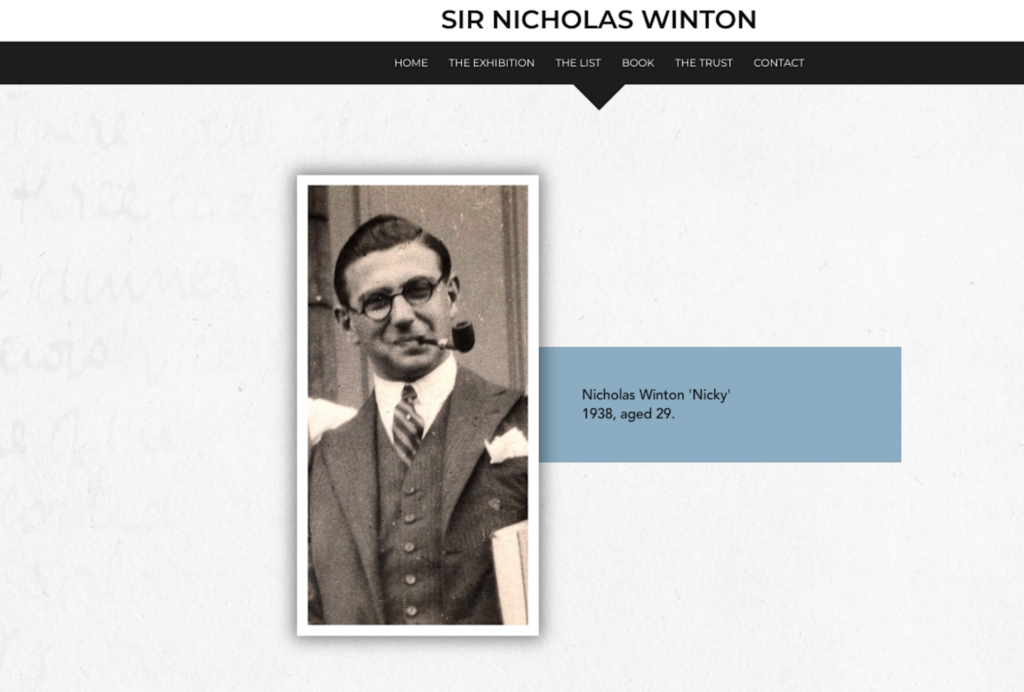

In December 1938, Nicholas Winton, a young London stockbroker, was looking forward to skiing in the Alps. Just before leaving, his friend Martin Blake, one of the BCRC (British Committee for Refugees) workers, called him and asked him to come to Prague and help. Indeed, Winton arrived and found that several organizations were working to rescue adults, but none of them dealt with children.

He returned to London, where he found that for the children, he had to secure an exit permit from the Germans, an entry permit from the British, acceptance into a British family that would care for them until the age of seventeen, and a deposit of fifty pounds (for a better understanding: 50 pounds in 1938 is equal to $3,500 today). Nicholas Winton later modestly downplayed this difficult task: “They needed help, but they didn’t know what to do. It was quite simple. Just ask. Just ask the right people in the right places.”

And so he began to act. He commuted between Prague and London, looking for permits, money, and families willing to take in the children. All this in the evenings and in his spare time, in addition to his job at the bank. Fortunately, he wasn’t alone. Essential was fellow Brit, Doreen Warriner, who took Winton to the refugee camps on the outskirts of Prague, where he saw Jewish refugees from the borderlands. Trevor Chadwick, head of the Prague branch of the BCRC, also had a significant role in that story. Or Beatrice Wellington, a Canadian who, to speed up the issuing of visas, often negotiated with the Gestapo’s criminal councilor, Karl von Bömelburg, who was not an ardent Nazi and did not directly oppose evacuation efforts. Last but not least, Winton’s mother, Babette, was also a great support.

The train with the first twenty rescued children left Prague on March 14, 1939. The same day that President Emil Hácha went to Berlin to meet Adolf Hitler, where he was given a choice between a military invasion and the establishment of a protectorate. (Hitler was not satisfied with the seizing of the Sudetenland, which was just “wishful thinking” when the Munich Agreement was signed, and on March 15, Germany occupied all of Bohemia and Moravia – Czechoslovakia ceased to exist the day before Slovakia declared independence and then allied themselves with Nazi Germany).

The eighth train left Prague on August 2. A total of 669 children were rescued, most of whom were of Jewish origin.

The Winton Train

When we say it was just before the war, it is – unfortunately – meant literally. A giant train with 250 children was supposed to leave on September 1, 1939, but because the Germans started World War II that day, the train did not go. Almost none of those 250 children survived the war – the names of only five survivors are known. Nicholas Winton later named the two saddest moments of his life – this ninth train and the sight of refugees from the Sudetenland, which started his whole effort.

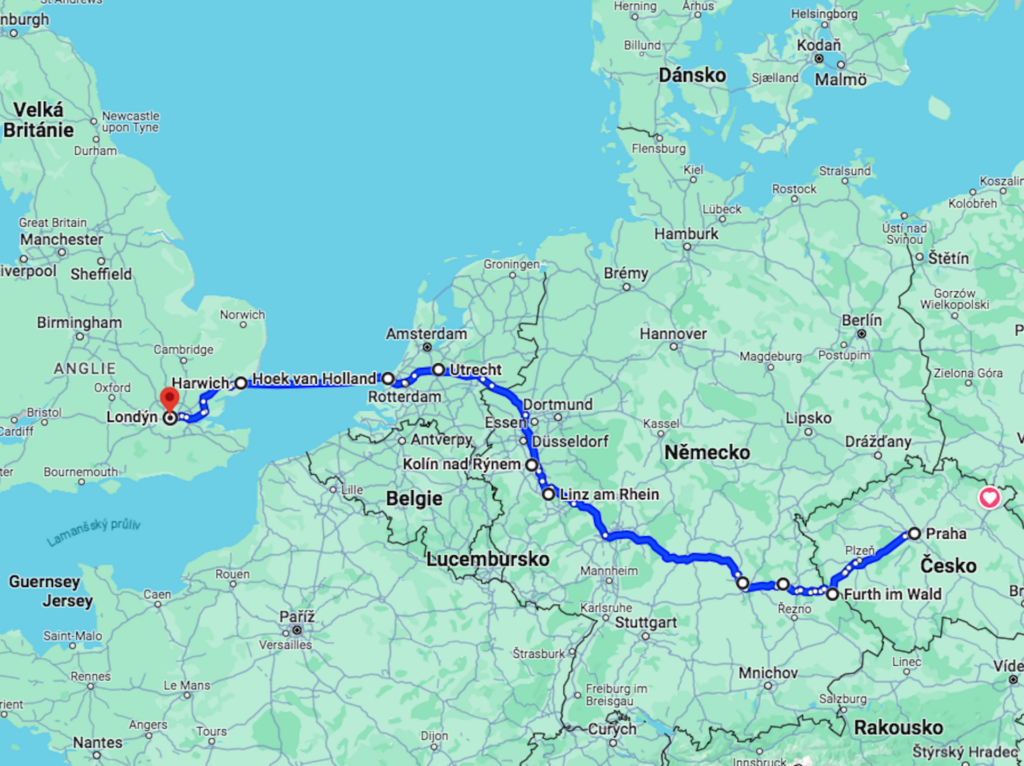

Seventy years later, on September 1, 2009, the tenth train left Prague. It was carrying 170 people, including 22 of Winton’s children. The trip lasted four days, during which the passengers had all the comforts, including sleeping wagons, a hairdresser, a beautician, a masseur, and medical service. The train followed the same route as the trains with children: Prague – Pilsen – Domažlice – Furth im Wald – Amberg – Nuremberg – Linz – Köln – Utrecht – Hoek van Holland – Harwich. The final station was London Liverpool Street. Sir Nicholas Winton was also waiting for it at the same platform where the trains of that time arrived.

The departure of the train from Prague was preceded by the unveiling of the statue of Nicholas Winton by the British author Flora Kent. She created three characters modeled after real people – of course, Sir Winton, the boy Hansi Beck, who arrived on the last train to England but unfortunately died of a middle ear infection after a few days, and the granddaughter of one of the rescued children.

The sculptor said at the unveiling of the statue: “Winton’s act was a rare ray of light in a time of deep darkness.”

Barbara Winton was also present at the unveiling of the statue and conveyed a greeting from her father before the train departed: “I give greetings from my father, who does not live in the past but in the future and therefore encourages young people to dedicate themselves to spreading good. Not necessarily in a big way; small deeds are enough. It is necessary to help and be vigilant.”

Four Sculptures of Nicholas Winton

Fortunately, this statue of Nicholas Winton is one of many. Just a year later, another was unveiled at Maidenhead railway station, west of London, in the Pinkneys Green section where Nicholas Winton lived. Sir Winton here sits on a bench looking at a book with pictures of the children he saved and the trains they left on. The sculpture was created by Lydia Karpinska and commissioned by members of Maidenhead Town Hall to honor their fellow citizen.

Even if Nicholas Winton saved “just” one child, he would be a hero. However, he saved 669 of them – estimates say that with their descendants, 6,000 people are alive thanks to him. Therefore, it is unsurprising that a statue commemorating this incredible heroism is also at Liverpool Street Station. It is pretty inconspicuous; you can find it in the passenger hall, within sight of the turnstiles at the exit from the platforms, and by the stairs to the metro station. It is a white marble cube with a standing girl, a sitting boy, and a suitcase. The same message in English, German, and Czech is on three sides of the cube: FOR THE CHILD – FÜR DAS KIND – PRO DÍTĚ.

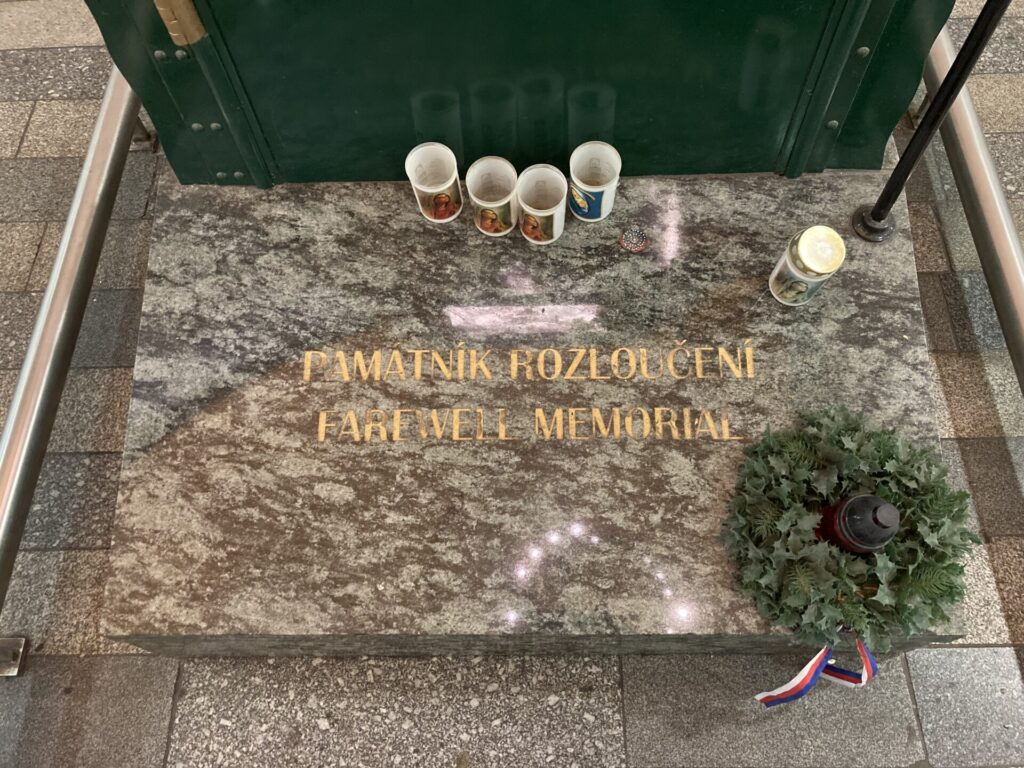

We must return to Prague, to the fourth statue located at the Main Railway Station. The statue of Nicholas Winton with children and a suitcase stands on the first platform. One floor below, under the main hall of the Art Nouveau Fanta building, we find a statue dedicated to the parents of the departing children.

As already said, only 50 years after the “kindertransports” did Winton’s children learn who had saved them. Sisters Milena Grenfell-Baines and Eva Paddock, recalling meeting Nicholas Winton, said: “But it was unbelievable for everyone. Suddenly, you are face to face with someone you thank for life. The feelings cannot even be described. In addition, for us, Winton’s children, the show answered the question: How did we get on that train? Who saved our lives in 1939?” – “I’m not even sure if my mother knew Mr. Winton personally if she ever saw him. I do not doubt that – even if I had asked her who organised the trains – she would have had difficulty finding an answer.”

However, there is one more massive moment in their sentences – the decision of parents who did not know what we know today. So they didn’t know the level of threat. And they were the ones who had to consider whether the coming Nazi threat was significant enough to balance the fact that they were sending their children somewhere into the unknown and not even really knowing what awaited them there.

They couldn’t quite believe it, yet they believed this was their children’s life decision. Most of those who sent their children to Britain did not survive the war. And as Věra Gissing recalled, at the moment of their death, they could be sure that their children were safe.

Another of Winton’s children, Hugo Marom, said: “Not only my parents, but all the parents who sent their children to a country they did not know, to people they did not know, and had no idea where the children were going, were heroes. They didn’t know about the concentration camps yet; maybe they had an inkling that the situation would be worse.”

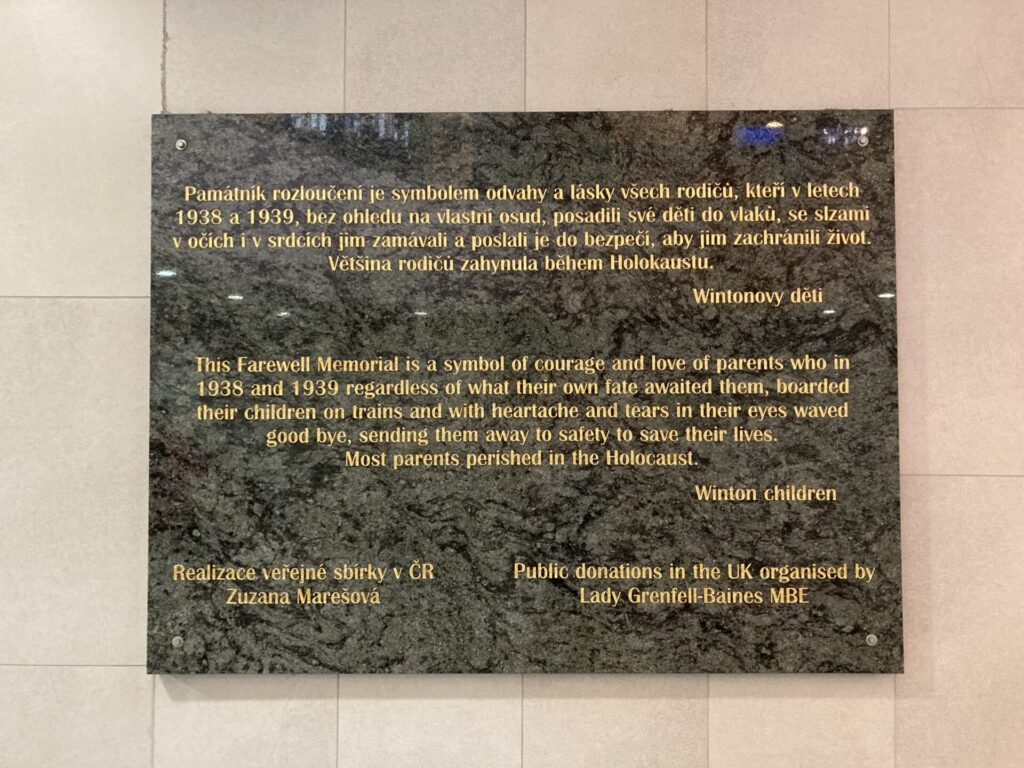

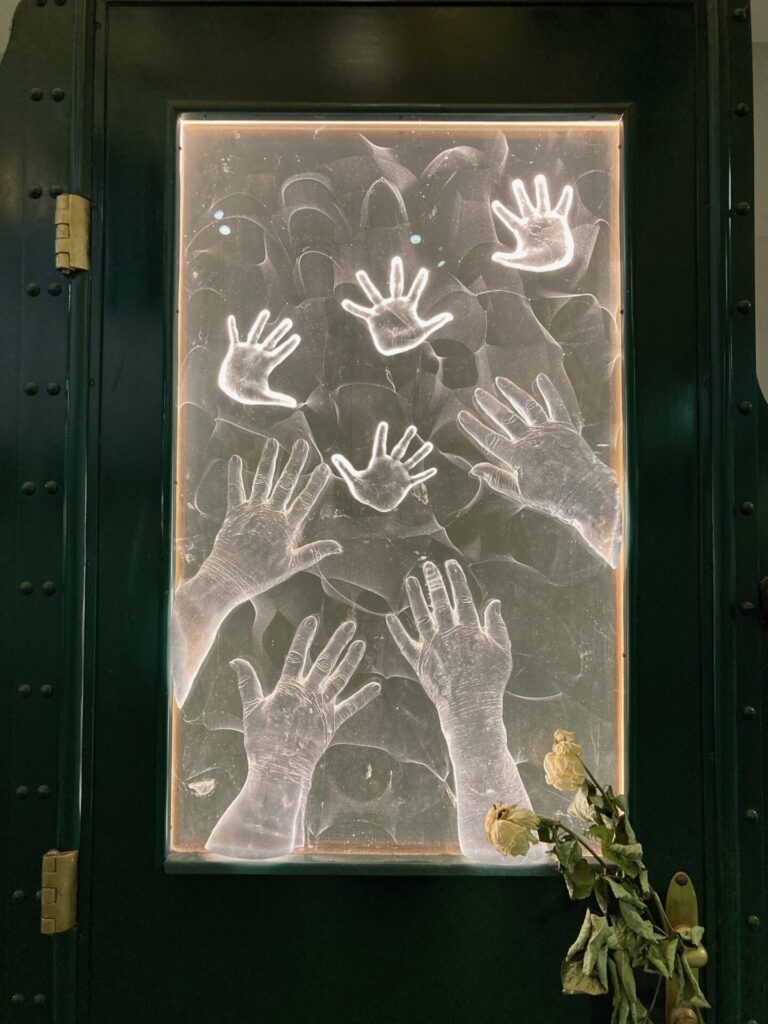

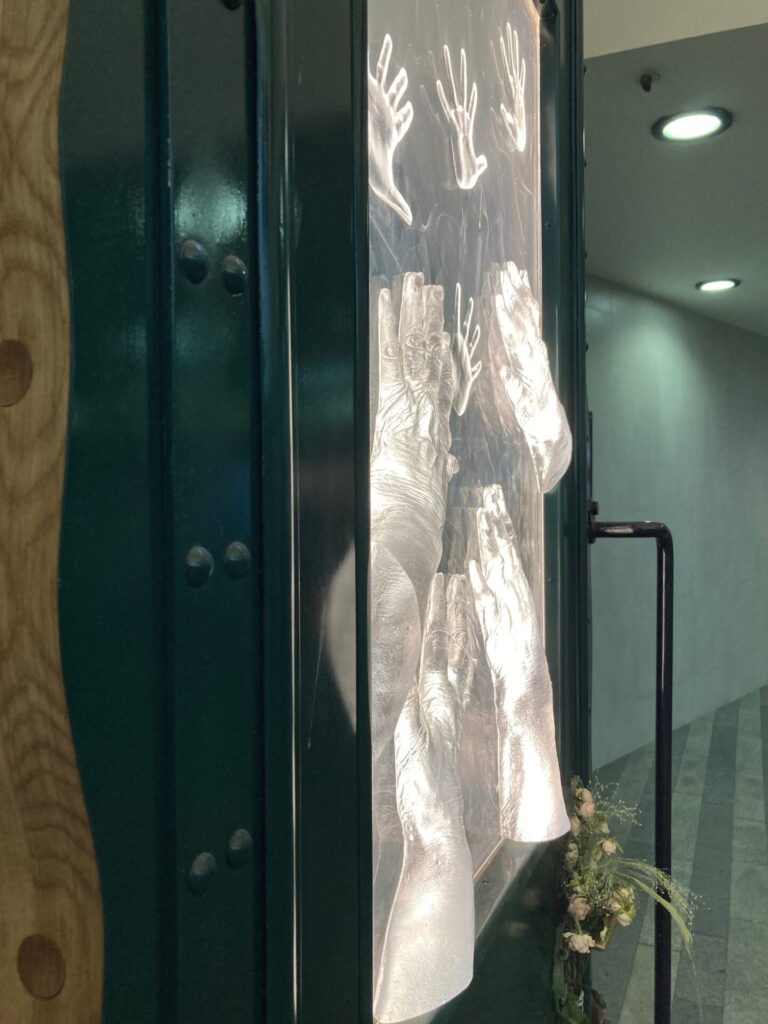

Hugo Marom came up with the idea to create the Farewell Memorial, which is dedicated to parents. Milena Grenfell-Bainesová and Zuzana Marešová then adopted the idea. The memorial consists of a replica of the authentic train door on which the children left. On the door’s glass, children’s hands are modeled on one side, and adult hands on the other. Glassmaker Jan Huňát made the castings based on the hands of both women and the great-grandchildren of one of them. The Farewell Memorial was unveiled on May 27, 2017.

Zuzana Marešová: “The farewell monument is an expression of gratitude to our parents for the second gift of life and is also a permanent memory of those who suffered the most and were the greatest heroes in the story of us, Winton’s children. There is perhaps nothing worse than giving up your child in the hope of saving his life.”

When the Name Nicholas Winton Is Mentioned in the Czech Republic, Doors Are Open Everywhere

In one of the interviews about himself with his humor, Nicholas Winton said: “I didn’t really keep it secret; I just didn’t talk about it.”

Of course, his story attracted the most attention in the Czech Republic. British director James Hawes commented on it with a sentence from the title: “Prague is a great place for filming in general; the local authorities are accommodating to filmmakers. Moreover, when the name Nicholas Winton is mentioned in the Czech Republic, doors are open everywhere. Czechs know his story well. They see it as part of their history. It is the result of Nicholas Winton saving your children.”

Slovak director Matěj Mináč, the son of photographer Zuzana Mináčová, who, as a teenage girl, survived several years in Auschwitz, was very devoted to the person of Nicholas Winton. His mom came from a Jewish doctor’s family; most of her extended family did not survive the war. Her fate was a significant inspiration for the film All My Loved Ones, which Matej Mináč made in 1999.

Already there, one of the key topics was the parents’ decision whether to send their son into the unknown with Winton’s Train. In 2002, Mináč filmed the documentary film The Power of Humanity, and in 2005, Mináč’s book Nicholas Winton’s Lottery of Life was also published. And in 2011, Nicky’s Family, a feature documentary genre, premiered.

So far, the last film about the story of Sir Winton is One Life by the aforementioned director, James Hawes. (It premiered on September 9 at the Toronto International Film Festival, and the London premiere was on October 12 at the BFI London Film Festival. The film has been distributed in the Czech Republic since February 1.)

Anthony Hopkins and Johnny Flynn portray Nicholas Winton in the present and the past.

In one of the interviews, director James Hawes recalled two beautiful moments:

* After the movie, Lord Alfred Dubs, one of the “kids”, approached me. He has been involved in helping refugees from different parts of the world for a long time. He is still active in the House of Lords. He confided in me that our film is like his life being projected onto him.

* (About the scene in the BBC TV studio): We shot this scene with relatives of the Winton children. When you see the movie, focus on the row behind Nicky. There are three sisters and a brother. One of them is really moved because she imagines what her father was going through at the BBC.

He also mentioned one experience that unexpectedly connected Nicholas Winton’s act with today’s reality: “We only had one day for a very emotional scene. The last Winton train was ready on September 1, 1939, but it did not run because the war had started. There were many kids in our extras who had never acted before. We explained to everyone what would happen that they would sit on the train, but then the soldiers started to take them out. It was shocking for the kids – the screaming and the confusion – but they coped brilliantly.

Moreover, we had to stop filming at one point because a train from Ukraine arrived on the opposite platform. Mothers and children were getting out of the wagon, screaming and confused. And we were standing by a replica of Winton’s Train.”

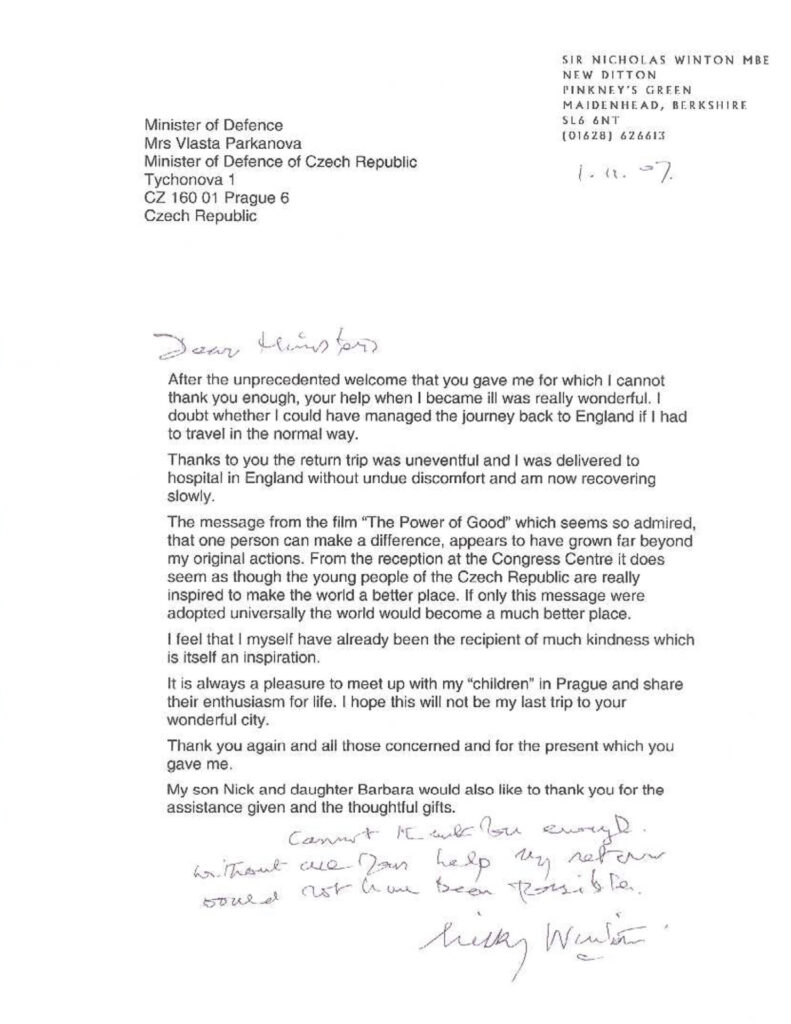

On the Czech Republic’s national holiday, October 28, 2014, Nicholas Winton received the highest Czech award, the Order of the White Lion, from President Miloš Zeman (in 1998, President Václav Havel awarded him the Order of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk). Nicholas Winton was already 105 years old, yet he personally came to Prague for the award. At that time, he also met seven of his rescued children who lived in the Czech Republic, and one woman arrived from Great Britain.

Nicholas Winton said modestly, “I was lucky to be in the right place at the right time to help fix the terrible things that were happening.”

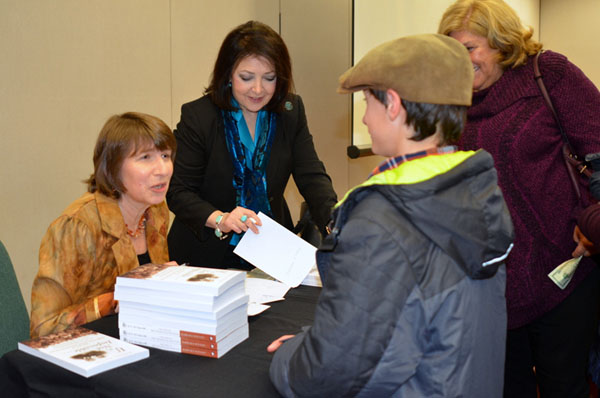

“I have discovered things from reading this book that I never knew about my own family and rediscovering episodes long forgotten. I had questions myself about certain incidents in my past and I have found the answers here. It’s strange to realize that Barbara knows more about my life now than I do.”

Good morning, Britain – Nicholas Winton’s son and one of the rescued children, John Fieldsend

Nicholas Winton and the Rescue of Children From Czechoslovakia, 1938–1939