One place in Prague is closely associated with the names of three influential men in Czech history. The second of them contributed to the separation of this area while the third joined it again after almost two hundred years. But in both cases it benefited the place. So what about the first one? He’s the one who built the much-needed Mouse Hole there two hundred years before the second one. Lapidary, one could say: digged out – disconnected – connected, but always benefitting.

Karel Chotek and His Granddaughter, Whose Death Started World War I

Almost every tourist knows this place, even if he is only interested in the Astronomical Clock, Charles Bridge, or Prague Castle in Prague. If someone looks at the bowing apostles on the Astronomical Clock in the Old Town Square, then crosses the Charles Bridge to Kampa and wants to see the Castle, he has three options. Either walk along Nerudova Street or up the Old Castle Stairs. Or he can choose a more convenient option and take tram 22 or 23 up the hill to the Castle.

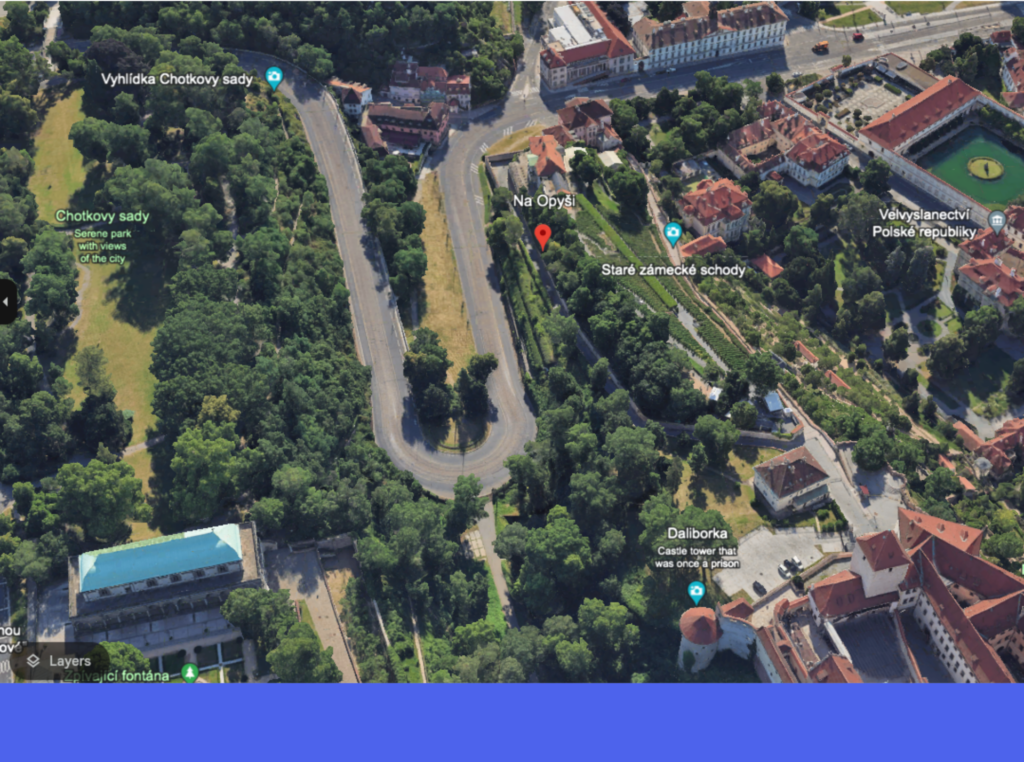

When the streetcar goes up from Klárov to Prague Castle, it passes through the almost opposite-direction turn at the gate to the Stag Moat. That curve and the street are called “Chotkova.” Both are named after Charles Chotek.

Charles Chotek (1783–1868) from Chotkov and Vojnín was the highest burgrave of the Czech Kingdom. In the past, the highest burgrave was the most crucial land official of the Czech Kingdom. He was president of the legislature, president of the provincial court, and commander of the army. Enormous power was, therefore, concentrated in his hands, so he was also the only local official appointed directly by the king; he was appointed for life and could only be deposed in exceptional circumstances. After the reforms of Maria Theresa and then her son, Joseph II, in the second half of the 18th century, the supreme burgrave gradually lost his de facto power until this function was abolished in 1848.

(By the way – Charles Chotek’s granddaughter was Žofie Chotková, the wife of the successor to the Habsburg throne, Franz Ferdinand d`Este. Both were assassinated in Sarajevo in 1914, which became the trigger for the First World War.)

Charles Chotek held this office from 1826 to 1843. He was highly active in organizing the large-scale construction and modernization of infrastructure in the Czech lands, especially in Prague where streets and squares were paved, sewers were installed, new buildings built, public gardens established, and tree rows planted. He placed great emphasis on good transport. The Charles Bridge was already congested with traffic, so the Chain Bridge was built near today’s National Theater (we are talking about the time 40 years before the National Theater was built). It is also worth remembering that under the leadership of Charles Chotek, the first railway line in continental Europe was established in 1828 – horse-drawn railway cars on the route from České Budějovice to Linz.

Last but not least, he designed and built the road from Klárov up to the Castle and transformed its surroundings into a park accessible to the public – it was the first public park in Prague. That is why this street was named “Chotek” in his honor in 1870, and the park was named Chotek Gardens.

Digging the Chotek Road was a fundamental step in the modernization of transport in Prague. From the 9th century, paths led through these places – from the ford over the Vltava to the Prague Castle and very likely also to Letná, which lies on the plain above the river, separated from the city center by a steep slope.

In the 1720s, Albrecht von Wallenstein had the Mouse Hole dug into the hill here, i.e., a passage through which even carriages could pass. (Albrecht von Wallenstein was the commander-in-chief of Emperor Ferdinand II’s troops. Wallenstein’s opponents, however, gradually convinced the emperor of Wallenstein’s betrayal. So the emperor had his former commander murdered in Cheb, but because he had a guilty conscience, he had three thousand funeral masses celebrated for Albrecht`s soul).

The Chotek Road went through the rock, making the construction difficult, but it greatly benefited traffic in Prague – even at the time of its creation, let alone today. A particular disadvantage was that the natural connection between the Opyš Hill, on which the Castle is located, and the Letná Plain was interrupted. That is why a footbridge was built here in the 1960s according to the design of architect Jaroslav Frágner, who was, among other things, the author of the reconstruction of the Bethlehem Chapel and Karolinum, which has been used since its foundation by Charles IV. as the historic seat of Charles University. (The ceremonial entrance to Karolinum is from the side of the Estates Theatre.)

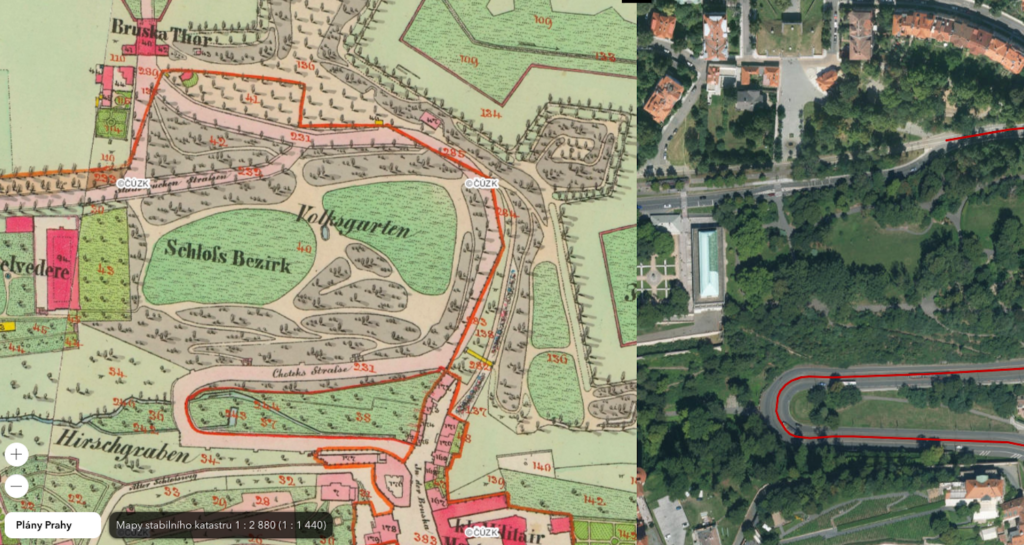

The maps in the pictures are from 1791 and 1842. Both show the present-day form of the Chotek Road on the right and its equivalent from that year on the left. The older map shows that part of the Stag Moat was taken for the construction of the Chotek Road. It’s logical. Wallenstein’s Mouse Hole, today’s Pod Bruskou Street, leads up a steep hill that trams could not climb. Even so, the tram track on Chotek Road is quite steep – that’s why a stop was established here in 1923, although practically no one got on or off it. But the stop forced the driver to stop the tram and start again. There was also a special official at the stop who checked that each driver actually stopped, got out of the car, marked on the special clock that he had stopped and then could start again. (The supervising official had a place there until 1935; until 1978, there was a “safety stopping place” – such places are on several lines in Prague and serve to increase the safety of tram traffic.)

Václav Havel, Who Opened and Cheered up Prague Castle

Because there is no sidewalk along Chotek Road, this made access to the Stag Moat much more difficult. This was rectified after 1989, when Václav Havel became president and made the Castle a friendly place full of culture. Thanks to him, places that were previously inaccessible to the public were reopened – including the Stag Moat, the Southern Gardens and the Royal Garden.

Thanks to him, the Stag Moat was made accessible from Klárov by a system of footbridges. However, above all, Havel and the architect Pleskot built a beautiful tunnel through the rampart under the Powder Bridge. Josef Pleskot commented on it years later: “Together, we were guided by the idea of removing all barriers, and not only in the technical sense. We were both greatly influenced by the belief that a new age was coming. I really enjoyed serving that idea, and I’m sorry it can’t come back.”

Personal and friendly ties helped Václav Havel with other projects as well. One of these projects becoming the newly built Orangery in the Royal Garden designed by architect Eva Jiřičná. During the fundamental reconstruction of the Southern Gardens, the Prague Heritage Foundation, founded by Václav Havel and today’s British King Charles III, participated financially. The above-standard friendly relationship between the two men played a large role in this as well.

According to Michael Žantovský, former ambassador to Great Britain and former Havel collaborator, the entire British royal family had a solid relationship with the Czech Republic. Václav Havel’s spokesman, Ladislav Špaček, recalled an incident from 1996 when Queen Elisabeth and Prince Philip were on an official visit to the Czech Republic. Václav Havel also wanted to show her his schnauzer Ďula. However, the dog was quite problematic, as Ladislav Špaček says: “It was an incredibly rude and aggressive dog that didn’t listen to anyone and bit everyone. Me too. However, in the presence of the British Queen, Ďula behaved incredibly. The dog absolutely melted as she suddenly sensed that she was near a person who had lived all his life among dogs and horses. She was such a strong personality that Ďula was as gentle as a lamb.”

It was a big moment for everyone; President Havel also remembered it in one of the interviews: “When I said goodbye to the Queen at Prague Castle, I brought my dog Ďula because I know that the Queen is a dog lover. That meeting went very well. Ďula didn’t make a curtsey, and maybe she didn’t feel the level of respect that we feel for the Queen. But she snuggled up to her, and the Queen petted her, which I was glad of.”

The Footbridge as a Symbol of Good Relationships

Václav Havel came from a family of builders. His grandfather Vácslav Havel, not only built apartment buildings but was also the first owner and builder of the famous Lucerna Palace. That is why Václav Havel was naturally interested in architecture as well.

Another project he initiated was the replacement of the dilapidated Jaroslav Frágner footbridge. In addition to aesthetic reasons, Václav Havel also had a symbolic reason for this. And that was the Kramář Villa. It was built between 1912 and 1915 by businessman and politician Karel Kramář, the first prime minister after the establishment of Czechoslovakia. From 1938, the villa was rented by the National Gallery, then the National Museum acquired the villa. Since 1952, the villa was managed by the Office of the Government and fell into disrepair. In 1991, it was declared a cultural monument. It was extensively reconstructed, and since then, it has served again as the residence of the Prime Minister.

Therefore, for Václav Havel, this footbridge was a symbol of good relations between the president and the government. The new footbridge was created according to the design of Havel’s “court architect” Bořek Šípek. Because Václav Havel was very interested in this project, he had the footbridge built mainly with money from sponsors and his own money.

The Epilogue

The footbridge was put into operation in June 1998. The photo shows the happy Havel couple on the newly built footbridge. It is an irony of fate that, after many years, in 2022, the already widowed Dagmar Havlová broke her ankle at the very moment she was walking on “their” footbridge.

The Chotek Gardens (Chotkovy sady), which adjoins Queen Anne’s Summer Palace (also called Belvedere), are almost the exact opposite. The sun shines in the garden of the Belvedere, and there is the rustle of many pairs of feet walking along its sandy paths. In addition, hundreds of people press their ears to the Singing Fountain to hear the sound of water falling to its bottom.

The Chotek Gardens were established in 1832 as the first public park in Prague. It’s a quiet, shaded place, sometimes evoking feelings of nostalgia and melancholy, with a beautiful view of Prague. Therefore, no one may be surprised by the somewhat gloomy monument of the Czech poet Julius Zeyer (1841-1901), with figures from his novels and poems and a water cascade. Strange place…

The Havel Footbridge naturally connected the Castle area with the Letná Plain. Right at the beginning of it, within sight of the Kramář Villa and the Hanavský Pavilion, there is a pond from 2022. The main function of this pond is irrigation and water retention and the related function in cooling the city. (On the territory of Prague, there are a total of 85 ponds owned by the city, 20 private ponds, 60 retention or rainwater reservoirs, and 4 large bodies of water. The largest of these is the dam in Hostivař in the south-eastern part of Prague, the level of which would fit more than 50 Letná ponds.) People are allowed to swim in the pond, but dogs are not, and boats are not allowed here. The maximum depth of the pond is two meters; the islet can be reached via a wooden pier.

Although Letná is high above the Vltava, the lake is fed by its water. This is done through the Rudolf Gallery. This is a tunnel more than a kilometer long, dug under Letná, built at the end of the 16th century on the orders of King Rudolf II, who built a huge pond (as big as half of Prague’s largest water body today, the Hostivař dam) in the Royal Game Reserve (now Stromovka Park).

At the beginning of the 19th century, Karel Chotek had an English park built in Stromovka, in which there were several bodies of water, some of which have survived to this day. (The yellow house in one of the photos is the exit of the Rudolf Gallery in Stromovka.)

Karel Chotek’s name is also associated with an interesting first, which also testifies to his social importance – family members were the first people to be photographed in Bohemia. It happened on November 3, 1839, at their castle in Velké Březno (Karel Chotek is the fourth man standing from the left). The very first photograph in the world (using the daguerreotype method, the predecessor of today’s “classic” photography) was created in 1837. Two years later, the French government bought this invention from Louis Daguerre for a lifetime annuity, and on August 19, 1839, the principle was donated to the world, free of charge . The photograph of the Chotek family, which was taken only two and a half months later, is thus one of the first photographic portraits in the world.

The name of the Opyš Hill is reminiscent of Na Opyši street, which leads from Klárov from the back past the Saint Wenceslas Vineyard to the eastern gate of the Castle. Opyš is a very infrequent word – it refers to the descending end of a rocky headland.

Chotek’s Turn also played a role in the life of the most famous Czech Nazi collaborator Emanuel Moravec. This was a man who went through a strange personality development, unfortunately for the worse. Moravec was a soldier, a patriot, Masaryk’s advisor, who stood in the honor guard at his funeral and carried the Czechoslovak flag at the head of the procession. He was also a journalist who wrote in the book Defense of the State that the biggest enemy of Czechoslovakia was Nazi Germany. Nevertheless, during the era of the protectorate, he became an enthusiastic promoter of Nazi ideology and promoted the vision of Europe united under German rule. Between 1942 and 1945, he was the Minister of Education and Enlightenment of the Protectorate Government. On May 5, 1945, the first day of the Prague Uprising, Emanuel Moravec drove along the Chotek Road from Klárov towards the Castle. When his car ran out of gas, and the driver got out of the car within sight of the Stag Moat, Emanuel Moravec pulled out a revolver and shot himself in the car.