If you say Prague and prayers answered or granted wishes, everyone immediately thinks of the Infant Jesus of Prague. However, right at the beginning of the Royal Road, there is a place where thanks are given for help in a very similar way, and it is also a place fundamentally connected to Czech statehood – the Czech anthem was born here.

That story took place at the beginning of the Royal Road, right next to the Powder Gate Tower. The place where the Municipal House stands today was once the King’s Court, and in the years 1383 – 1484, it was the seat of six Bohemian kings, which Vladislav Jagiellon had returned to Prague Castle. (Charles IV’s son, Václav IV, moved from the Castle to the King’s Court, allegedly for a sense of greater security and also because of disagreements with Charles’ widow, Elizabeth of Pomerania (Alžběta Pomořanská), whom Charles married after Václav’s mother, Anna Svídnická, died at the age of just 23 while giving birth to another son).

How a Musical Hit Became the Czech Anthem

Directly opposite the King’s Court, the Church of St. Joseph was built in the middle of the 17th century as part of the monastery of the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin (a branch of the Franciscan Order, which is inspired by the life of Francis of Assisi). At the end of the 18th century, the monastery was abolished by the decree of Joseph II. In the middle of the 19th century, military barracks with a large riding hall and stables was built on the site of the abolished monastery and its garden.

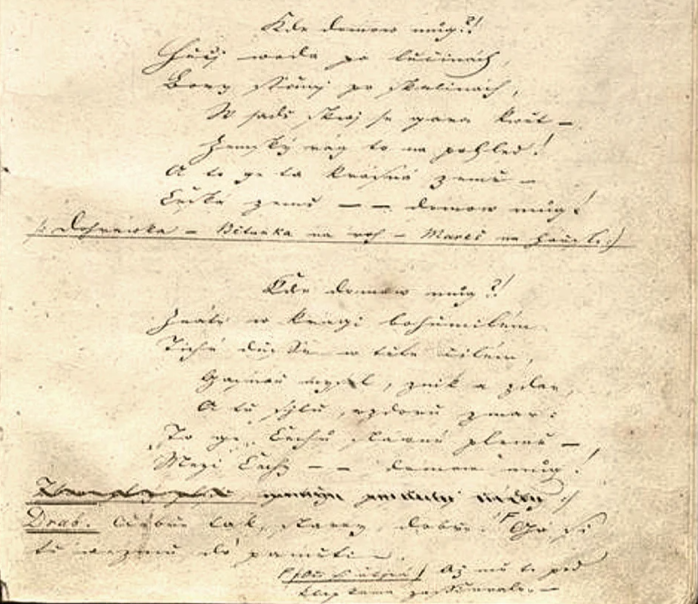

One of the soldiers who lived in these barracks was the writer, playwright, and actor Josef Kajetán Tyl. He also wrote the song “Where Is My Home?” for one of his dramas. The play was not a great success, but the song became wildly popular. It was first performed in December 1834 and soon became a hit. It was played at dance parties and in theaters, and people sang it on the street. It could be heard at various gatherings, and people started to take off their hats in respect.

Soldiers during the First World War sang it when they left for the front and in the trenches; the song praising the Czech landscape gave them the strength to fight. Its popularity has been compared to the Hussite hymn “Who are God’s Warriors?” (Ktož jsú Boží bojovníci), whose author is the priest and prominent speaker, Jan Čapek. (This chant was so famous and significant for Czech history that Bedřich Smetana quoted its melody in the symphonic poem “My Country”, in parts Tábor and Blaník.) After the dissolution of Austria-Hungary and the creation of an independent state, Tyl’s song became the Czech part of the Czechoslovak anthem; after the breakup of the common state in 1993, it became the Czech anthem.

Thank You, Tadeášek

The barracks were abolished in 1993, and the entire building was demolished; only the facade remained. The Palladium shopping mall was built behind it. The stables remains, which has been reconstructed. Its military past is remembered by a stylized horse’s head.

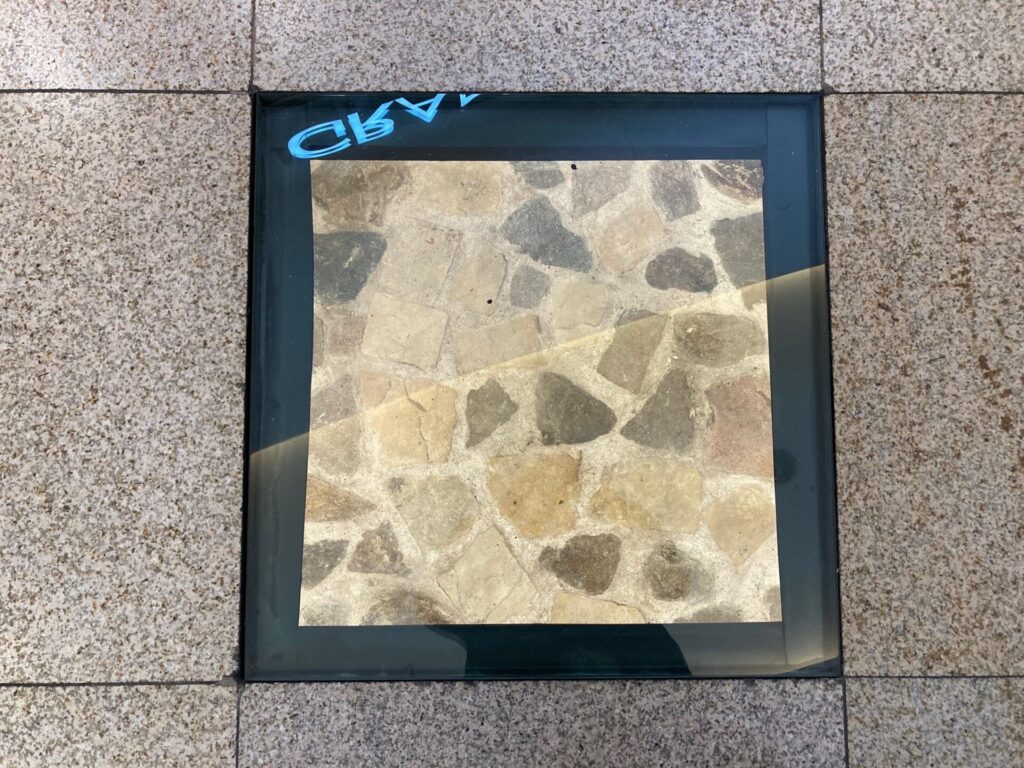

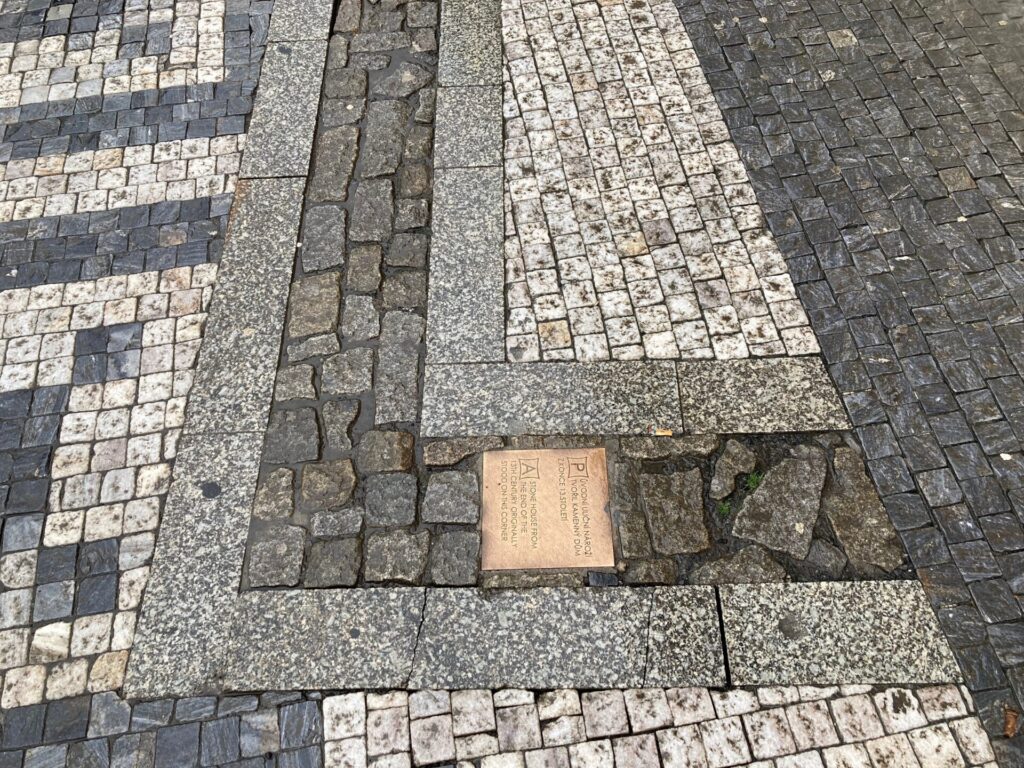

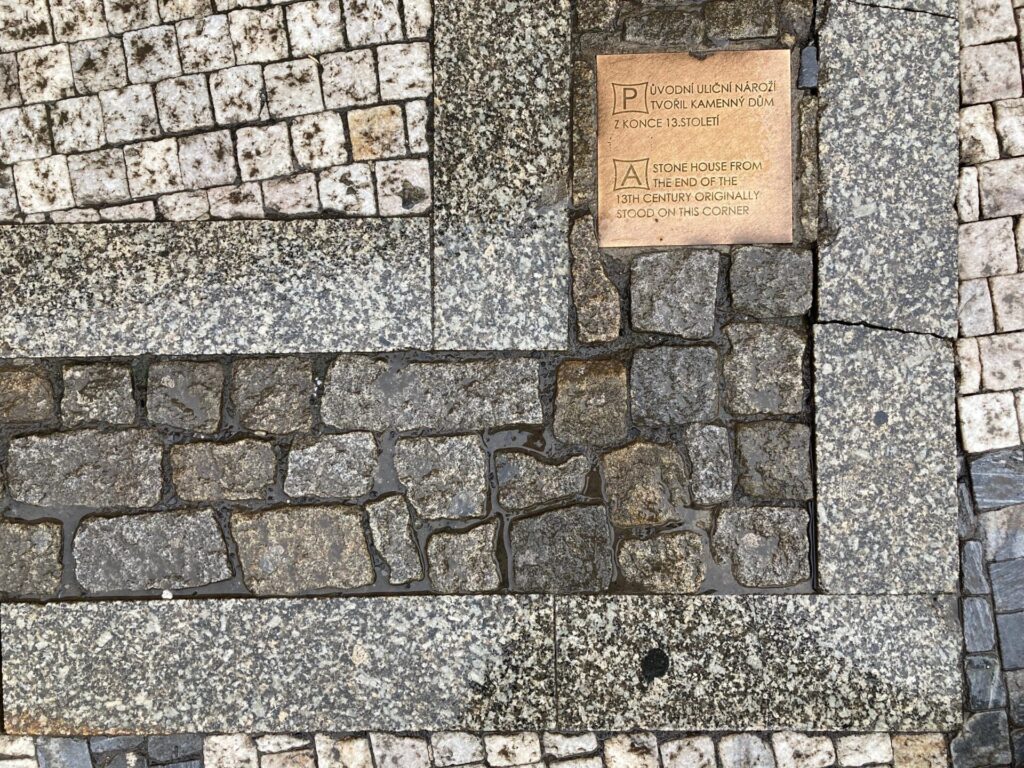

In the modern commercial space, the centuries thus merge. During the archaeological survey of the construction site, the foundations of three stone Romanesque houses were found. Today, they are part of one of the cafes with an escalator running above them. In the floor, there are several glimpses of the foundations of the monastery – in contrast to the neon lights of 21st-century shops…

Fortunately, the church of St. Joseph was preserved; the Capuchins also rebuilt the classicist building to the right of the entrance to the church’s atrium for their needs.

(In the atrium, there are sandstone statues of Saint Jude Thaddeus and two angels. The painting above the entrance to the church, whose golden framing glows in the dark, depicts St. Joseph with the baby Jesus. On the sides of the entrance to the atrium of the church are statues of Francis of Assisi and John of Nepomuk.)

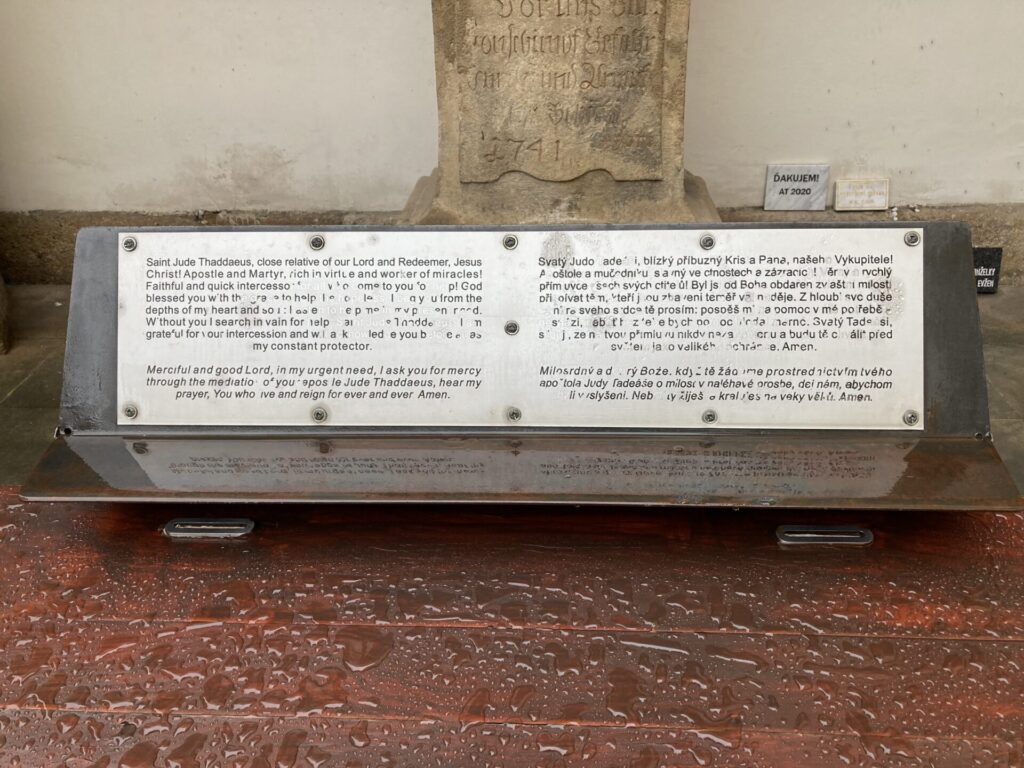

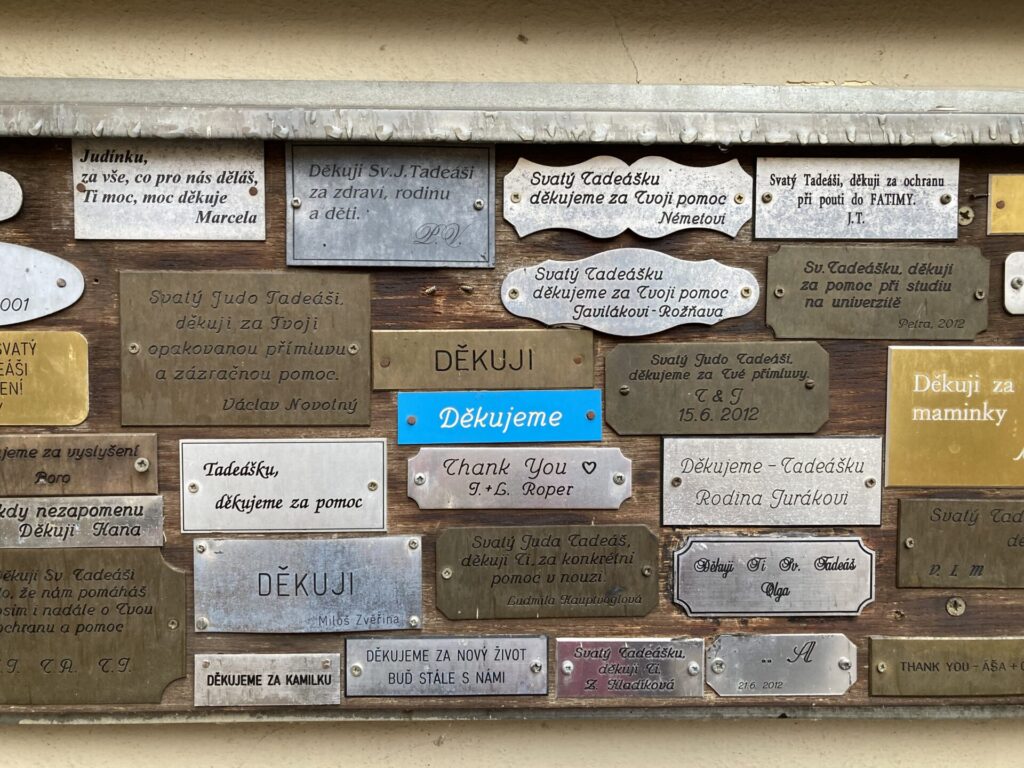

As you enter the atrium, you will see three giant statues standing on the left side. It is a statue of Saint Jude Thaddeus with two angels standing by his side. On the left side are candles that people light as thanks; on the right side, there are large boards with many metal slices on the wall. People give thanks for them, too, for constant help and support, success in a college exam, birth of children, family health, or the gift of marriage.

This is because Saint Jude Thaddeus, one of the twelve apostles of Jesus, is the protector in hopeless situations. Whether in general life or health. People are grateful for this protection, which is evidenced by the often very familiar addressing of the apostle, in addition to the diminutive “Tadeášek”, for example “Táda” or “Judínek”.

Cannonballs Everywhere You Look

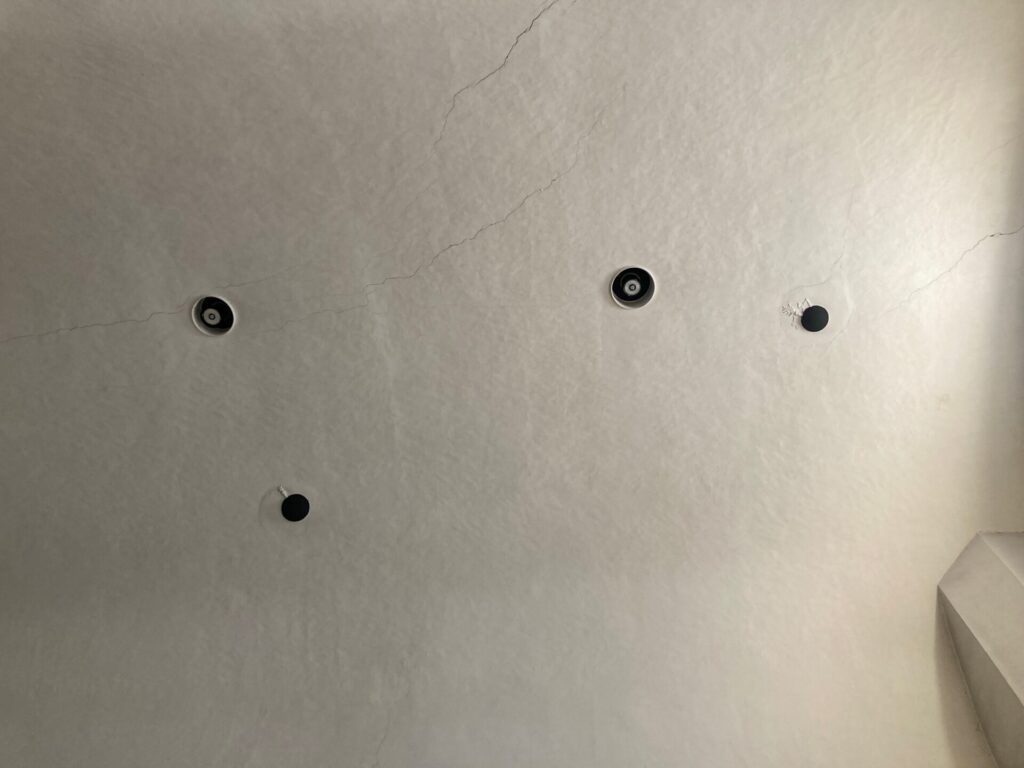

If you look towards the barrel vault of the church, you will undoubtedly be interested in the two cannonballs above your head. One of them even has the plastic number 1757 in the plaster, which reminds us of almost seven weeks in May and June of that year, when the Prussians besieged Prague during the so-called Seven Years’ War.

It was the most destructive siege in the history of Prague, in which tens of thousands of Prussian soldiers took part, who fired almost 60,000 cannonballs, more than 20,000 grenades, and half a thousand incendiary missiles at the city. A quarter of all buildings in the town were destroyed or damaged. The targets of the Prussian missiles were mainly civilian objects – with this pressure the Prussians wanted to break the resistance of the residents.

There was a shortage of medicine and food in the besieged city. Paradoxically, fortunately, this was preceded by a crucial battle on the outskirts of today’s Prague – near Štěrboholy. There, the Prussian army won (the battle is considered the bloodiest battle of the 18th century), and the Habsburg army retreated to Prague, where it was also surrounded by soldiers and thousands of military horses. This defeat thus helped to protect Prague from an even greater famine…

Thank You, Baby Jesus

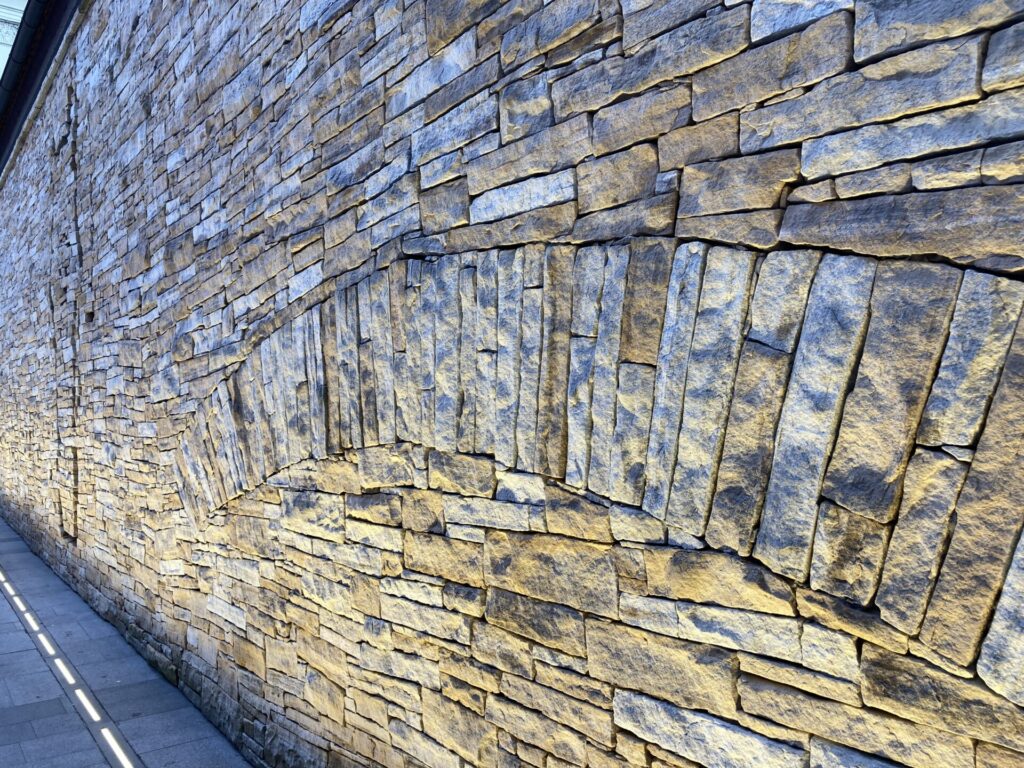

The remains of the Prussian shelling of Prague are even more visible on another object of the Capuchin brothers – the wall of the Church of Our Lady of the Angels, which is part of the monastery in Hradčany.

This is also an object where people go to give thanks – but not for help in trouble; rather, it is thanksgiving and “looking forward” to Christmas. And it is related to the nativity scene here.

The tradition of building nativity scenes was founded by Francis of Assisi – in 1223; after returning from Bethlehem, he prepared a manger with a live donkey and an ox for the participants of the midnight mass in a cave near the village of Greccio. The first nativity scene in Bohemia was built in 1562 in the Clementinum. Paradoxically, it was the banning of nativity scenes that helped spread the tradition of creating them. Empress Maria Theresa and afterwards her son Josef II (previously mentioned), banned the construction of nativity scenes in churches because, in their opinion, they were “unworthy children’s toys for the church”. And when there were no nativity scenes in churches, people began to secretly build them at home. So, in addition to traditional biblical figures, there are also figures that people knew from their surroundings – artisans, miners, or shepherds.

Prague’s most famous nativity scene is the one in the church in Hradčany. There are always lines of people who come to see the Nativity scene in front of the church at Christmas – last year it welcomed approximately 25,000 visitors.

The Baroque nativity scene has 32 life-size human figures and 16 animals. The larger figures have polychromed heads and hands carved from wood. The others have wooden skeletons and paper mache bodies. The nativity scene was created around 1730. It was originally built in the church, but since 1967 it has been permanently installed in the side corridor.

The peculiarity of this nativity scene is two sheep that bleat and nod their heads after throwing coins into the shepherd’s hat. This has been happening since 1902 when one of the brothers moved the sheep’s head by pulling the string behind the nativity scene. Today, the bleating and ringing of the bells are handled electrically.

Baby Jesus brings Christmas presents to Czech children. And when a child throws a coin into the shepherd’s hat and the sheep nod their heads and bleat, it’s also thanks for the fulfilled wishes…

Secretary of the Capuchin province and rector of the church, Jiří Bonaventura Štivar, with the head of a donkey. Today, in this nativity scene, the Baby Jesus is not warmed by a donkey and an ox but by a deer and a mouflon. The reason for this is purely practical – they are stuffed heads of real animals that the church received as a gift.

The original mechanism was nodding the sheep’s heads.

Jiří Bonaventura Štivar – thank you for the excellent tour of the nativity scene.