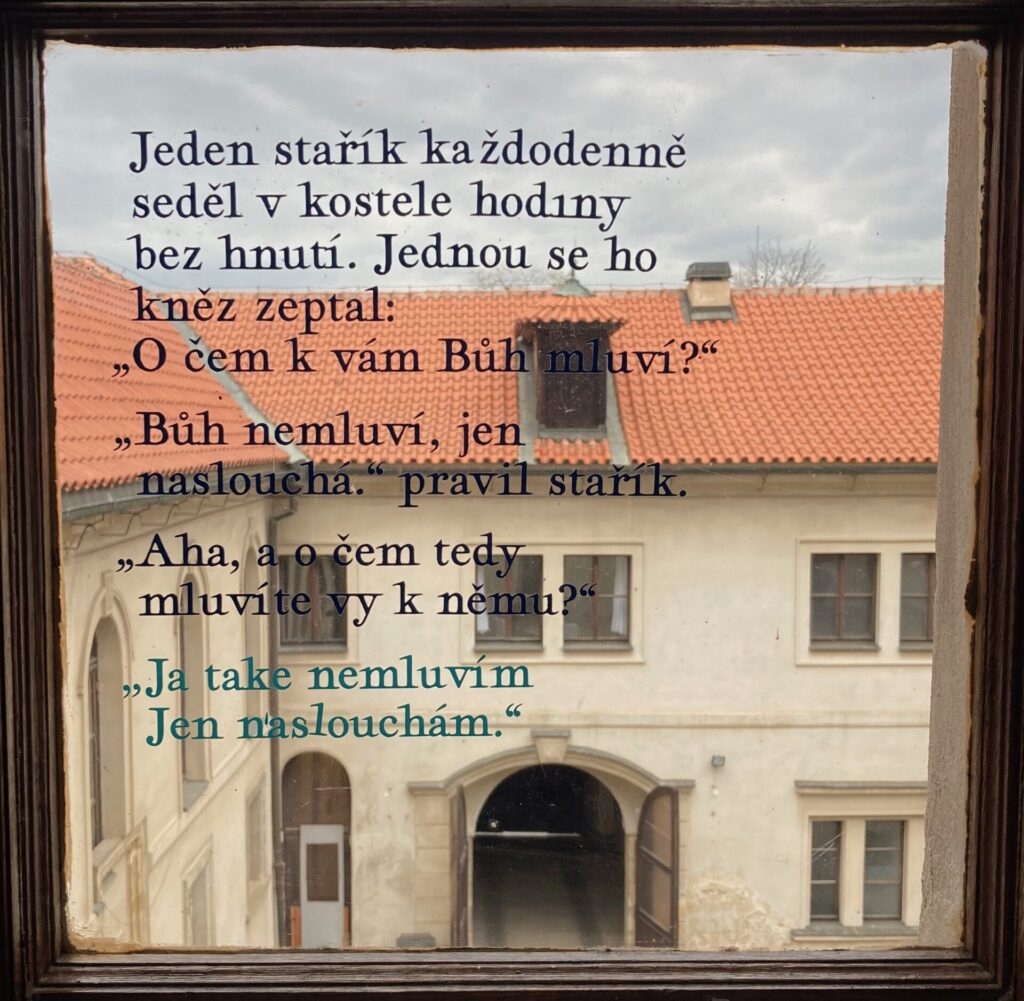

An old man sat in church every day, motionless for hours.

One day the priest asked him: “What does God speak to you about?”

“God does not speak, he only listens,” said the old man.

“Oh, and what do you speak to him about?”

“I don’t speak either. I only listen.”

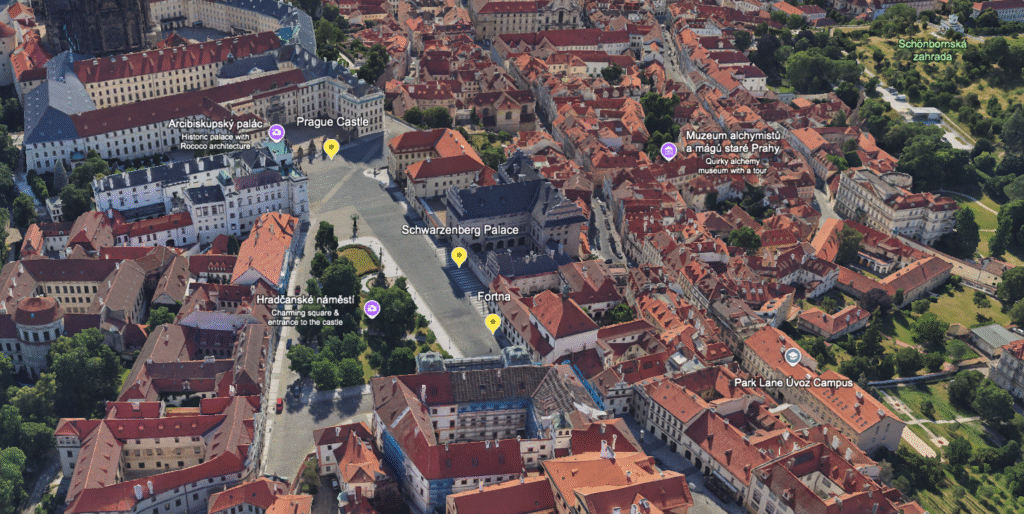

At the start of Hradčany Square, right next to Schwarzenberg Palace and within sight of The Matthias Gate of Prague Castle is Fortna (“portal”). Until recently, it was one of the most closed places in Prague, but today it is open to the general public.

The Barnabites and Joseph’s Reform

The Gothic church of St. Benedict has stood here at least since 1353. There were Renaissance-style houses around until the mid-17th century. (Among them was the house of Bohuslav Hasištejnský of Lobkovice (1461-1510). He was a prominent Czech nobleman, traveler, prose writer, and poet whose poems were among the masterpieces of his time. He was also a poet who wrote exclusively in Latin (because he considered Czech a barbaric language).

After the great fire in Prague in 1541, the church was rebuilt, and from 1654-1660 the Barnabites bought the surrounding houses and added a monastery to the church. However, the monastery and the church were confiscated in 1786 by order of Emperor Joseph II. He then abolished a third of the Czech monasteries by decree. He wanted to preserve only those that directly served the people – caring for the sick, being involved in charity, or active in education or science. It was a very controversial decision, and Joseph’s mother, Empress Maria Theresa, disagreed with it, so Joseph only carried it out after her death (although very immediately).

However, Joseph’s reform aimed not to suppress faith but, on the contrary, to ensure that every person had a church within a maximum of an hour’s walk from their home, which at that time was not the case in mountainous regions. Therefore, a third of the orders were abolished at this time, but it was also when the largest number of new churches were built. And since Maria Theresa had already introduced compulsory school attendance in 1774, for least six years, this also meant that schools were established in parish buildings so that every child had a maximum of an hour’s walk to school. This applied not only to boys but also to girls, which should be noted was a big deal back then.

To Joseph’s credit, it is worth adding that he guaranteed all members of the abolished orders a pension of 150 gulden (gold coins) and double that if they went to serve the state as clergy. This money was paid out of newly established religious funds, which were funded by the sale of monastical property. In Bohemia and Moravia, these funds totaled more than 20 million gulden.

Hospitals were set up in the confiscated buildings. Some were given to the army, and many properties were sold off. One example including all of these: the St. Agnes Monastery housed warehouses, workshops, and apartments for the poor.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to believe that these sales were free of corruption. Monastical furnishings were often sold for an estimated price without regard to their actual value, including their historical value.

The Arrival of the Carmelites, the Communist Interlude, and Considerations About Leaving

Joseph’s successor, Emperor Leopold II, donated the monastery on Hradčany Square to the Order of the Discalced Carmelites in 1792. During Joseph’s reform, the Carmelites were expelled from their original monastery church of St. Joseph on Josefská Street in the Lesser Town.

By the way – the former Carmelite monastery garden is today not only the oldest preserved garden in Prague but also one of the most popular. It’s called The Vojan Gardens (Vojanovy sady).

After the communist putsch (1948), the monastery was confiscated as part of the extensive repression against church orders in 1950 and the building was rebuilt into a luxury hotel for prominent communists. What a paradox – including the fact that political prisoners also worked on the construction. Including the fact that when a kind of communist rehabilitation commission was held here in 1963, it was officially called the Barnabite Commission.

In 1992, the Carmelite sisters returned to Hradčany, but the building gradually stopped meeting their needs. The area is not very large, less than 200 meters in circumference, with only 0.6 acres. The sisters would leave the monastery only very rarely (to see a doctor, etc.), so they needed a sufficiently large garden to live in, and they did not have one in Hradčany.

The closed community of sisters was also bothered by the increasing noise. The building is on the busiest tourist route, and movies are shot on Hradčany Square. Concerts and other events for crowds are held there. Right below the atrium of the building are the Town Hall Stairs (Radniční schody), where there are two very noisy pubs, from which the shouting and laughter of the guests are carried into the silence of the atrium above their heads.

Therefore, the sisters decided to move in 2005 but spent the next eleven years searching for a suitable plot of land. They finally found one in Drasty, a part of the Klecany municipality, about 10 km as the crow flies north of their previous home.

Construction of the monastery in Drasty

The Discalced Carmelites live in a papal closure, with great emphasis on solitude and silence. For both financial and organizational reasons, neither of these is compatible with constructing a church and monastery.

The Hradčany complex was bought from them by a benefactor of the male Order of Discalced Carmelites for 150 million crowns, but the amount only covered 60% of the costs of building a new headquarters. The sisters, therefore, knew that they would save money by physically participating in constructing the complex themselves. So they not only did auxiliary work such as clearing the buildings of the original farm, from where they removed dozens of containers of waste, including thousands of old tires from a former car repair workshop. But they also cultivated the land and the future garden and could handle working with a chainsaw or driving a tractor or a small excavator. In terms of contact with the surrounding area, this meant not only organizing work with companies and communicating with workers but also organizing brigades of volunteers who came to help on the construction site.

The rest of the budget for constructing the Drasty complex was covered by proceeds from public collections, sales of the sisters’ handicrafts, and renting an apartment building that the sisters built in the complex. The monastery is now not only a home for the Carmelite sisters but also offers accommodation for individuals and groups in separate spaces, with 33 beds in 15 rooms. Lectures or retreats can be held here. As the sisters say: “We create a space for silence, prayer, and sorting out thoughts.”

We’re Opening the Door, Come On In!

The area in Hradčany has completely changed since the sisters left. It used to be a quiet, peaceful place, with the gates always closed, no matter what time of day or night you walked by. Today, two brothers live here, who are part of the community of Discalced Carmelites at the Infant Jesus of Prague. But anyone can come to the monastery and the church of St. Benedict.

The monastery has regular opening hours for anyone who wants to visit. Every year, dozens of weekend courses and retreats are held here for the public and various communities, as well as meditations, workshops, and other programs.

One of the options on the Fortna website is called Just Stop. On Fortna, you can stop for a moment, take a breath, and sit. Meditate, read, meet, and chat, or just be for a while.

The area also includes the Church of St. Benedict, the first mention dates back to 1353 (the monastery complex was added to the church in the mid-17th century).