In 2003, director Jan Hřebejk made the film Pupendo, which depicted the grotesque reality of life in communist Czechoslovakia in the 1980s. Soňa Červená (SČ) played a prominent, although not significant, role in it. An opera singer of world importance, she was almost unknown in her homeland. If anyone associated her surname with art, it was because of the “Červená sedma” cabaret, which her father founded in 1909.

Her international career began with a dramatic escape from East Berlin, where she was working at the State Opera. After World War II, the city was divided into four occupation zones: the Russian one, which became East Berlin, the capital of the German Democratic Republic GDR), a satellite of the Soviet Union, and the American, British, and French ones, which created West Berlin, an island of freedom in the midst of unfreedom and, in this sense, a symbol of the Cold War.

Since 1952, West Berliners had not been allowed to enter the GDR but could enter East Berlin. However, this ended in 1961, when the Berlin Wall was built. SČ: “That was the end. The Wall walled everything up – all my plans, hopes, and wishes. So I decided to go through the Wall.”

Citizens of the German Democratic Republic were not allowed to go anywhere, but up until the Wall was built, foreigners from East Berlin could enter West Berlin. There were eight crossings for this, the most famous of which was Checkpoint Charlie. As a foreigner, Soňa Červená could continue passing through Checkpoint Charlie, but she felt that the situation was worsening. At that time, she was determined to leave for the West, and she chose the date of January 9, 1962, because nine was her lucky number. However, on January 4, a friend called her to say the window had closed. Checkpoint Charlie was closed. Soňa had just cooked lunch. She turned off the stove, picked up her dog and her handbag, and drove to the crossing. There, a young East German soldier told her that she had to get permission from her embassy to pass through.

SČ: “I knew that would be the end, so I told him – and I said that word for the first and last time in my life: COMRADE, I’m singing in Leipzig tonight and I have to go here with that Mercedes to have the clutch fixed, it’s getting annoying again. I’ll be back in two hours and I’ll go to Leipzig. And if you don’t let me go now, you’ll have to deal with Leipzig Radio. You’ll have problems. And the boy had such beautiful brown eyes like a doe and he said: ‘Then go. But it’s the last time.’ And it was the last time.”

She went through the crossing, turned the corner, and her knees shook: “So. And now my life begins again.”

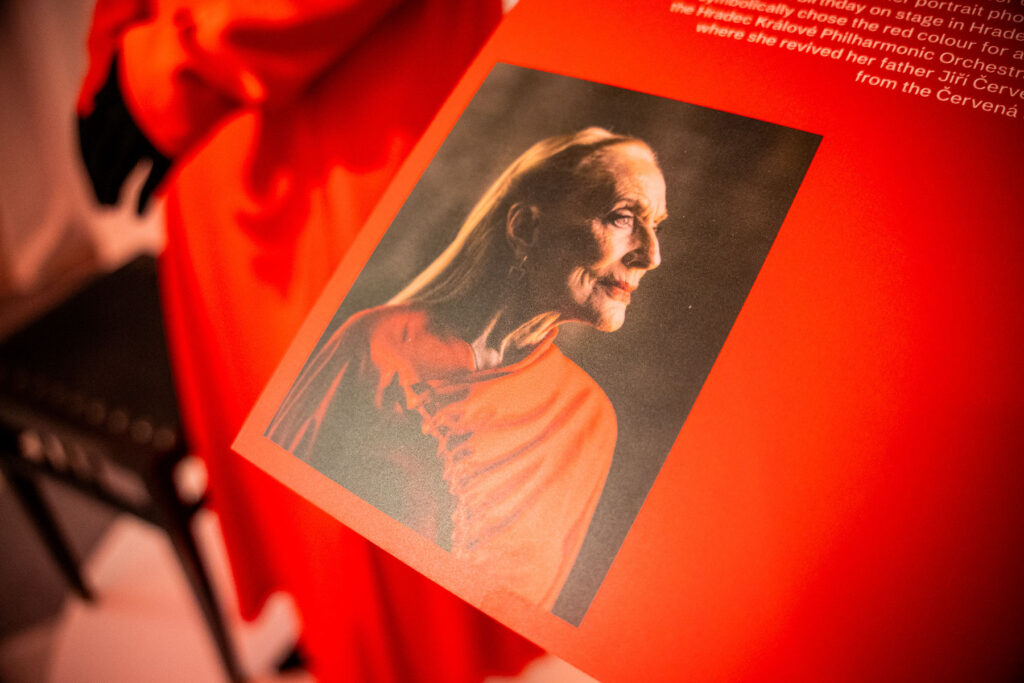

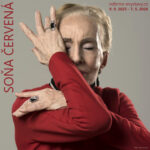

A minute-long video – trailer for the documentary Červená, introduces Soňa Červená in her own words. But what is a minute compared to the more than 97 years she lived… Her life was long, colorful, and beautiful, but not easy. That is also a reason to tell more about her.

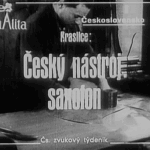

Why Isn’t the Saxophone Called a “Redophone”?

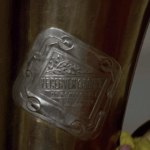

Soňa Červená’s great-grandfather was Václav František Červený, a manufacturer of wind instruments that were among the absolute world leaders in the second half of the 19th century. The fame of his instruments is also evidenced by the fact that when Richard Wagner finished writing the series of operas The Ring of the Nibelung, he added the words “tuba Cervený” to the score.

The company’s heyday ended with the death of Václav Červený. The company was taken over by his sons, but World War I made it very difficult. Another blow was World War II, after the Communist putsch in 1948, the company was nationalized and incorporated into the state-owned company, Amati Kraslice. The company continues to sell Václav Červený’s instruments to this day.

Between 1844 and 1889, Václav Červený filed 44 patents, but as Soňa Červená recalls, he was sometimes too frugal, so he did not patent everything. It got the worst of him with the saxophone: “The so-called saxophone was invented by my great-grandfather. At the exhibition in Paris, he – I won’t say he (Adolphe Sax) stole it, he appropriated it and had it patented. Because my great-grandfather didn’t have the money to patent it at the time, which was too expensive.” (And since “červený” means “red”, the saxophone could have been called, for example, a redophone.)

Václav Červený loved theater and theater people. That is why in 1877, he initiated the construction of a theater in Hradec Králové. He organised a fundraiser and asked the city council to provide land for free. After her return to her homeland, Soňa Červená played there in Dürrenmatt’s The Visit of the Old Lady: “My great-grandfather was a great patriot. He was appointed an honorary citizen of the city, a co-founder of Sokol, and the chairman of the Hradec Association of Theater Volunteers, and he contributed with his influence, commitment, and money to the construction of the Klicpera Theater. You understand how I feel when I enter this theater.”

Carmen!

Soňa Červená died on May 7, 2023. In September of that year, she would have been 98 years old. She stood on stage for 75 seasons, performing 5,500 performances on five continents. Her dominant field was opera, where she sang in more than 100 roles. But she was also a star in musicals, operettas, dramas, and melodramas.

Agnes was a housekeeper for Soňa’s parents (her mother and stepfather), who went out almost every day. Agnes kickstarted Soňa’s love for opera. Agnes was in love with a tenor at the National Theater, and since the family lived on Na Struze Street (we will talk about this apartment later), just a few dozen meters from the theater, Agnes took Soňa to the theater very often – almost every day and even twice a day on weekends.

That was when the world of opera opened up to Sona Červená. And that was when Carmen enchanted her: “When Mary Cavan lifted up her skirt and a dagger flashed under her garter, I was so excited that I started carrying a pocket knife in my stocking. My future was clear to me: I would not become an actress. I would be an opera singer.”

Mary Cavan, wife of the National Theatre opera singer Otakar Mařák, once invited Soňa Červená’s mother to tea. Soňa was allowed to go with her and was completely captivated when “her Carmen” invited her into her dressing room where she was allowed to see and try on her theater costumes, including the Carmen costume. However, it only hung limply on the eleven-year-old girl and was a great disappointment. However, this did not affect her dream, so that as an adult Soňa Červená sang Carmen a total of 156 times, in three languages and on three continents, in the world’s greatest opera houses.

Mother and a Slap to the Gynecologist

When the gynecologist told Soňa Červená’s mother that she was pregnant, she was not happy about it. She declared that she did not want a second child, and one that would be born under the sign of Scorpio and ruin her ball season. When the doctor told her that it was too late for a radical solution, she was so angry that she slapped him and left the doctor’s office.

Soňa was then born in Borůvka’s sanatorium, a hospital for wealthy clients. One of the great paradoxes of her life is that in the same sanatorium, 23 years later, her mother died after a harsh interrogation by the State Secret Police. Soňa then “stole” her mother’s dead body at night so that she could bury her with dignity…

SČ: “I admired my mother because she was beautiful and very funny. But I don’t know a relationship like the one I had with my mother. / We never understood each other. She didn’t understand me, and I didn’t understand her. / Home is a word that always makes me a little embarrassed, because I never really knew the idea of home. I don’t regret it, I don’t complain, but I think that the fact that the word “home” didn’t become embedded in me helped me go the way I did. / The theater became my home. There I felt at home, safe and happy.”

The Tragedy of the Desire for Possessions

Soňa Červená’s parents divorced when she was very young. Her mother Žofie soon remarried the wealthy Karel Veselík, who died in 1938. The fortune from her second husband was too large to go unnoticed. First, the Germans wanted to take it from her, and after 1948, the Communists. After the “German attempt”, she ended up in the Ravensbrück concentration camp, and after the Communist one, in the grave.

Soňa’s father, Jiří Červený, whom her mother had forbidden her to see for many years, was imprisoned in Terezín. His situation was also made worse by the fact that his file stated that he was a composer, and the Germans thought that meant he was a communist (in Czech: komponista / komunista). And so seventeen-year-old Soňa was left all alone in a huge apartment on Na Struze Street. Inexperienced, defenseless, and clueless. And also without money, so she occasionally sold some valuables from the apartment, silver, or a painting, to have food. One day, the apartment was taken away and given to a German family who were to “protect her”. However, the family had a twenty-five-year-old son, René, who regularly raped Soňa. He promised her that he would help her mother, saying that his father had unlimited power with the Gestapo. So she tolerated it for a whole year. He never helped her in any way.

In May 1945, Soňa was sought out by three women from the burned-out village of Lidice who were living, along with 181 other women from that destroyed village, in Czech barracks in Ravensbrück with her mother. They told her how her mother had given them courage: “God will send her to you, because she really protected us.”

After the war, the mother walked from the camp to Prague; the shortest route is 450 km (almost 300 miles). Soňa was engaged to her future husband, František, at the time. They waited only a short while for her mother to return before getting married. SČ: “She came almost barefoot, emaciated, wounded, miserable, shaved bald, but not broken. I was getting married in a fortnight.”

The property ultimately proved fatal to Žofie Veselíková. In July 1945, she was arrested again because of it and accused of collaborating with the Nazis. (Perhaps also because she was from the Sudetenland and had German citizenship.) She was later cleared of this incrimination. After the Communist putsch in February 1948, she was arrested again. She was forced to sign a cooperation agreement with the Communist secret police, and was released. In November 1948, she was arrested again.

After two weeks of not knowing anything about her mother, Soňa received a phone call from a young medical student, Jiří Filoun, the son of a former pianist from the “Červená sedma”. SČ: “He was stuttering when he told me that they probably had my mother’s dead body at the autopsy.”

It was her! When the orderly brought the body covered with a white sheet, he said to her, “Thank you for coming. If no one were to come forward, they would have had to put her in a common grave in the cemetery in Ďáblice the next day.” She grabbed his hands. “Could you give her to me?” – “Why not? Come and get her tonight.”

Žofie Veselíková allegedly died after a six-hour interrogation. Yet the official in the secret police office denied it. She reportedly committed suicide with poison she had in her handbag. When her daughter wondered why her arrested mother was allowed to keep her handbag, he told her sharply, “If I were you, I wouldn’t ask so many questions. We have proven your mother’s planned escape across the border.” She eventually received two death certificates. The prison doctor stated the cause of death to be poison, the pathologist indicated pneumonia. Soňa had her mother’s body taken away by a funeral service at night and buried her secretly in the Vyšehrad Cemetery the next day.

Artistic Career Before Leaving for Germany

Otherwise, the period from the end of the war to the putsch in February 1948 was very happy for Soňa Červená. She was newly married and in love. Her husband had his chocolate factory back. They had a beautiful apartment and a rich social life.

She was also successful at work (let’s remember that she was 20 years old in 1945). In 1947, she made her film debut as an actress in Poslední mohykán (The Last of the Mohicans), which is still popular today (in the film trailer, Soňa Červená is the girl on the left, in a lighter dress).

She also celebrated great success at the Osvobozené Theater (Prague Free Theater), in the musical Divotvorný hrnec (the Finian’s Rainbow). The song “U nás doma” (At our home) quickly made her famous. Although it was not yet her beloved opera, this experience was also very valuable to her. It was performed eight times a week, a total of 318 times, and thanks to this regular workload, her voice became stronger and more confident.

Along with her success with the audience, Soňa continued to yearn for her mother’s recognition. One day she invited her to the theater, to see the play Pěst na oko (Fist in the Eye). She got her the best ticket and played for her all evening. Amid the endless applause of the audience, she wanted to honor her mother with a bow and a long look, but she was no longer sitting there. The next day she told her daughter that she could not stand such bullshit. After that, she never visited the theater to see her again.

On February 25, 1948, a Communist putsch took place in Czechoslovakia and the Communists began to rule with an iron fist. Clouds began to gather over Žofie Veselíková and her daughter. František’s factory was nationalized and he himself was to be arrested. Fortunately, he received a warning and when they came to arrest him. He was no longer at home. They saw each other only once more. František urged his young wife to flee with him. The escape was prepared and paid for dearly. However, she refused. She did not want to leave her mother, and they both thought that what was happening was just a terrible dream and would soon pass. Beloved František fled alone, and they never saw each other again.

On October 13, 1948, the communists banned her from acting: “In the case of the actress and singer Soňa Červená, it was decided that the named person should be distanced from all theater, film, and radio activities with immediate effect.”

The director of the Osvobozené Theater was Jan Werich, a highly respected actor and director at the time (and still is, although he died in 1980). When Soňa’s world collapsed, Jan Werich invited her to his office: “I Could help you escape, if you want?” – Thank you, but I have no reason to escape.” – “That’s what I wanted to hear from you.” Within a week, he managed to cleanse Soňa Červená and she was able to go back on stage.

And she realized one important thing: “When I stood on stage again, I understood what theater means to me, that I cannot and do not want to live without theater, and that I will never let anyone take it away from me again. Theater became my family, my home, my everything.”

Political Pressure

The pressure on her did not stop even after her mother died and her husband had fled. SČ: “I was afraid for my life. And even more afraid that they would forbid me from singing. That was the only thing I wanted, could do and had to do. Their agents were constantly hot on my heels, ringing my doorbell at all hours of the day and night, waiting at the theater, and everywhere I went. They wanted to intimidate me, to crush me. They tried again and again to force me to sign a contract to work with them. At first I did not understand what they wanted from me. They explained to me that as an actress, and with my knowledge of German and French, I could easily get into social circles that might interest them. When I energetically objected that I could neither spy nor inform, they said clearly: “But you can act, right? And you won’t play much if you are reluctant to work with us.”

She told them during one of the interrogations: “I’m not a spy, I can only act and sing. So I can’t sign anything for you because I can’t fulfill it. And I don’t want to.”

A friend told her at the time, “Darling, in this country, you have to be shorter than grass. And you became too much for them to handle.” Perhaps by a stroke of fate, she received an offer that same day to become a member of the opera company of the Janáček Theater in Brno. She went there, sang, and was offered a contract. She decided to escape the pressure of the communist secret police by disappearing from their sight to the much smaller Brno, and she accepted the offer. She then sang in Brno for seven years, thanks to which she further advanced professionally. Then it was time for another change. And that change was called East Berlin.

Pressure from the secret police of the totalitarian state eventually led to her emigrating: “I couldn’t live or sing without freedom. And I didn’t want to torn apart by the secret police. That’s why I emigrated with a heavy heart and lived and sang abroad for thirty years.”

Only once did she think about returning to her homeland. That was during the political détente in 1968. At that time, she was rehearsing in Munich under the baton of Rafael Kubelík, a world-class conductor and a legend among Czechs in exile. He seemed to her inaccessible, taciturn, uncommunicative. Then he asked her if her father was Jiří Červený. When she said yes, his face lit up: “Those were the days.”

She took advantage of the moment to ask, “Maestro, they say things are starting to loosen up in Czechoslovakia. Would you come back?” He immediately stopped smiling: “I don’t believe a word they say. You’ve been warned.”

SČ: “There was no defiance in his voice – more like sadness. The conversation ended, but it revealed a lot. I got a clear answer to all my doubts, hopes. That’s why I didn’t come back. That warning probably saved my life.”

On August 21, 1968, Soňa Červená was at the Bregenz Festival. There, she received news that Czechoslovakia had been occupied by the army of the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact countries: “I desperately missed the Prague embankment, for the first time in years. Now tanks were rumbling along it.”

For all this, it is paradoxical that after 1989, Soňa Červená’s name appeared in the archives of the Ministry of the Interior in the list of StB agents, i.e. the Communist secret police. Below was the agent’s “funny” name: Fialová. (Červená = red, Fialová = violet). Soňa Červená ignored it at first. It was beneath her to defend herself that she had not cooperated. It was only when she was supposed to star in the production Zítra se bude… (Tomorrow Will Be…), which deals with how the communist regime sent politician Milada Horáková to the gallows in the 1950s, that she hired a lawyer to clear her name. Of course, she won the court case and on October 29, 2010, the court ordered the Ministry of the Interior to delete Soňa Červená from the list of StB collaborators.

To Germany

In 1958, Soňa accepted an engagement in Berlin, first at the Unter den Linden Opera and in 1962 at the Deutsche Oper. During her three years at the Berlin State Opera, she sang in fifteen productions in 193 performances.

In Berlin, Soňa Červená was contacted by André von Mattoni, Herbert von Karajan’s personal secretary, and told her that von Karajan would like to hear her. When she came to West Berlin with her accompanist and sang the first aria for him, he invited her to sing another. She replied that she did not have the sheet music, but that she could perhaps sing for him Cherubino from The Marriage of Figaro.

SČ: “And so the great von Karajan got up, went to the piano, pushed my pianist aside, and started playing with me. Well, it was wonderful. Von Karajan was my pianist. And then he got up from the piano and said quite quietly: “Wir sehen uns in Salzburg.” (We’ll see you in Salzburg.) And he left.”

In the spring of 1961, news spread that a wall was to be built between East and West Berlin. When Soňa Červená sang at the Salzburg Festival, André von Mattoni contacted her again and, on behalf of Herbert von Karajan, offered her an immediate engagement at the Vienna State Opera if she did not want to return to Berlin.

She was very hesitant because it would mean leaving for good. She would never be allowed to return to her homeland. She decided to feign a heart attack and stay in Salzburg for a few more days. Then, a visitor from the Czechoslovak embassy told her, “When you feel a little better, we will take you safely by car to Prague.” This made her decide faster. She went to Vienna and signed the contract.

However, the feeling of satisfaction did not come. Deep down, she felt that political connections had driven her to this. And she did not want to leave the Berlin State Opera, which had meant so much to her career, so suddenly. She asked to cancel her contract and was granted it with the words: “Apply if you ever get out.”

Longing Forbidden, Longing Averted

Her escape to the free world in early January 1961 was not an impulsive idea, although in her case it really meant: turn off the stove, take the dog and the purse, and quickly leave. But she had been thinking about it for a long time.

On November 29, 1961, after a concert in Prague, she saw her father for the last time. They had a farewell conversation in the famous restaurant U malířů in the Lesser Town:

“What would you do if I told you right now that I might not be coming back?”

“Soňa. I’ve lived my life and you have to live it for yourself. Don’t turn to anyone and don’t ask anyone.”

“Dad, we’ll stay here for a while. Shall we have another glass of wine?”

“No. Everything in moderation, little girl.”

That was the last time they saw each other. Soňa Červená escaped to freedom at the beginning of January 1962, her father died in the middle of the year. On January 3, 1962, she wrote him her last letter before leaving for the West. It began with the words “my beloved “: “The most magical family fireplace could not replace the magic of the theater dressing rooms and sleeping compartments, the moments of stage fright before a performance and the feeling of happiness after it. (…) Wow, Dad, I could write to you endlessly, but I have to leave. Please understand and forgive me! I am yours, S.”

Both of her books, in which she writes about her life and her singing career, have the word “longing” in their titles. The one about life in the free world, but without the opportunity to see her homeland, is called Longing Forbidden. The one about her second career in the Czech Republic, after November 1989, is Longing Averted.

On this topic, she mentions that she forbade herself to miss her homeland, because it wasn’t even her homeland when political opponents of the totalitarian regime were imprisoned and hanged there. And it also had a self-preservation aspect: “I wasn’t allowed to miss it, I forbade myself from doing so. I’ve seen several emigrants whose lives were ruined by homesickness.”

However, this does not mean that she had given up on her home. As she writes about her first visit to Prague after 1989: “I stopped by the Vltava River, breathed in the fresh water air and thought to myself: this is home.” She returned because of the Vltava River and its fresh water scent. And because they speak Czech here, she has retained her excellent Czech even after thirty years away from her homeland: “They took everything from me, but they will not take away my Czech.”

After her entry into the free world, she rented a lovely apartment and applied for political asylum. For about a week, she was in a refugee camp during the day, where she was routinely interviewed by an American immigration officer. When they were having lunch together, he said to her, “It’s a shame we didn’t know you when you were still in the East. You’re so beautiful and famous, you’d make a great Mata Hari.” She immediately replied, “I turned down Mata Hari in Prague, and I would turn her down for you, too.”

Meanwhile, several newspapers had headlines: An Eastern opera star was seeking asylum. The director of the German Opera in West Berlin immediately contacted her – and offered her a two-year contract. Thus began her immensely successful nearly thirty years in the free world.

Return

In 1961, the construction of the Berlin Wall was the final impetus for Sonia Červená to emigrate. In 1989, the demolition of the Wall was the first impetus for her return…

The fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, triggered the collapse of communist regimes throughout the then “Eastern Bloc.” This was preceded by May 1989, when the Hungarian government had the roadblocks removed from the border with Austria, and people from the German Democratic Republic who wanted to emigrate began to travel to Hungary. The German government therefore introduced a visa requirement for entry into Hungary, and Germans began to travel to Prague. In August and September, the streets of Prague were blocked by hundreds to thousands of Trabant and Wartburg cars, unlocked and with the keys in the ignition. Or with a sign reading “Feel free to take it.” This was because East Germans fled to the West German embassy and were later allowed to travel by train to West Germany thanks to an agreement between Berlin and Bonn, the capitals of the divided German republics. The first wave of Germans leaving this way was followed by another five thousand who climbed over the fence of the West German embassy in Prague, and another two thousand stood in front of its building in Lesser Town. By November 9, 1989, when the Berlin Wall fell and crossings between the two parts of divided Germany were opened, 15,000 refugees from East Germany had passed through the West German embassy in Prague.

On November 17, 1989, the Velvet Revolution broke out in Prague. Soňa Červená: “I watched the breathtaking events in Prague on television day and night. I didn’t even dare to believe that the threat “forever and never otherwise!” had come true. (In full: “With the Soviet Union forever and never otherwise!”) I wanted to go there with open arms. But suddenly I realized that I was a stranger there. Out of the whole world, I am most of all a stranger in my hometown. No one can know who I am, where and why I wandered, what I did, what I accomplished. Thirty years of an interrupted movie.”

In her busy schedule, she found four free days for Prague only in March 1991. It was a shock. The Vltava was dirty and the bourgeois houses on its banks, once colorful, were now gray, sad, neglected. For thirty years, Soňa Červená was forbidden from her homeland – so consistently that her radio recordings all had the warning: DO NOT BROADCAST! Written in large letters on them, and the very popular movie The Last of the Mohicans appeared on television, but new titles were made in which her name was no longer there.

However, she cherished her relationship with her homeland for all those decades when she was persona non grata here. Of course, she also encountered reactions that hurt her. “You had a good time, but what about us who stayed here? Do you even know what heroism it was to survive here?” Many only saw her success and money and were not willing to admit how much hard work was behind it. Including the fact that when they called her one morning from the theater in Brussels asking if she would fill in for Leoš Janáček’s Her Stepdaughter, with the addition “Your plane is leaving at 12.30,” she packed her bags and flew off to sing.

But she received a wonderful welcome in one curious situation – when she was almost run over by a car. It happened on Pařížská Street, when a car was speeding towards her. She had just enough time to jump out of the way. The driver slammed on the brakes, jumped out of the car and started hugging her: “Oh my God, Mrs. Soňa Červená! We almost ran over Soňa Červená! Can you forgive us?”

Finally on the Stage of the National Theater

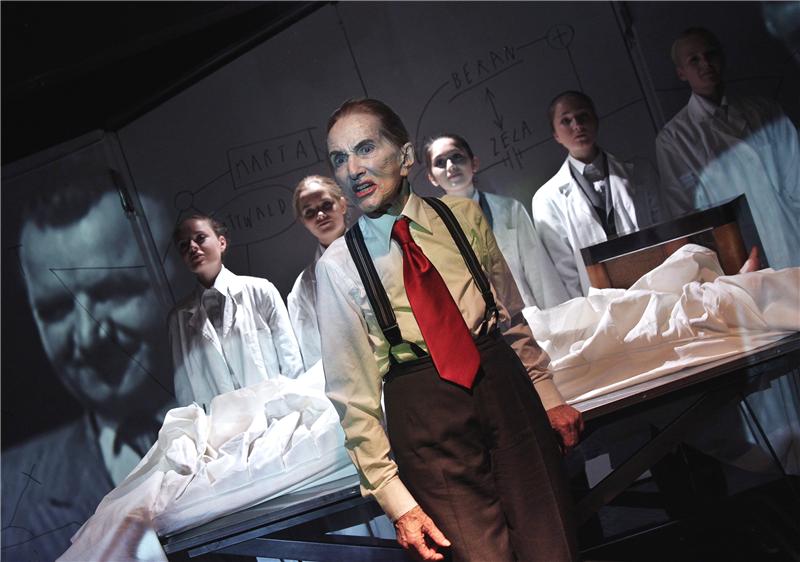

Before leaving for Brno, Soňa Červená made several guest appearances on the stage of the National Theater, but she was barred from performing for political reasons. After her return to her homeland, however, nothing stood in the way of this dream. She first took it on in 2002, in Janáček’s opera Fate, directed by Robert Wilson. SČ: “I’ve wanted it all my life. And he, an American director, made it happen for me.” In other productions from the National Theater’s opera and drama production (Tomorrow Will Be…, The Makropulos Affair, The Fate, 1914, Toufar, The Bloody Wedding, etc.), she played on the stage of the “Golden Chapel”, as the theater is generally called, more than 250 times.

(Josef Toufar was a priest whom the State secret police wanted to use to discredit the Catholic Church. Because he did not want to confess to something he did not commit, he eventually died after four weeks of cruel torture after an operation in the Borůvka sanatorium. That is, where Soňa Červená’s mother died after a six-hour interrogation.)

In 2006, the theater’s opera director Jiří Nekvasil told her: “Mrs. Červená, you know what? Choose a theme, we will pay for the music and six performances in the next season at Kolowrat.” (“Kolowrat” was the chamber stage of the National Theater in the Kolowrat Palace, right next to the Estates Theater for many years.)

Soňa Červená met with composer Aleš Březina to agree on who the new opera should be about. It was clear that it would be about some great Czech woman. They were thinking about Božena Němcová, Eliška Krásnohorská or Ema Destinnová: “And suddenly we both fell silent for a moment and said in unison: Milada Horáková.”

Milada Horáková was a Czech politician who was executed by the ruling communists in 1950. She was executed after an extensively staged political trial, the primary goal of which was to intimidate any opposition and allow the communists to have a firm grip on the situation after the putsch in February 1948. Like the mother of Soňa Červená, she was imprisoned both by the Nazis during the war and by the Communists after the war. She also survived the Nazi trial and prison, but not the Communist one. She herself refused to ask for pardon, but many figures advocated for it, including Albert Einstein, Jean-Paul Sartre, Winston Churchill, and Eleanor Roosevelt. The communist president Klement Gottwald, who knew Milada Horáková well because they were both members of parliament – she for the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party, he for the Communists, did not grant her pardon.

The regime’s callousness is also evidenced by the fact that during their last meeting, a few hours before the execution, they did not allow Milada Horáková and her daughter to hug each other. And also by the fact that the letters written by Milada Horáková the night before the execution remained in the archives of the Ministry of the Interior. The family did not know about them throughout the totalitarian period. They were only handed over to her shortly after the Velvet Revolution by the Minister of Justice, Dagmar Burešová.

SČ: “The greatest heroine of the 20th century for me was Milada Horáková. Learning this role was a profound experience for me, because I saw our entire generation and, most importantly, my entire life in her. And perhaps I could give her what she deserved.”

Milada and Bohuslav Horák were warned, but they refused to leave the country. When the police came to their house, their housekeeper had enough presence of mind, she seized the police and Bohuslav Horák managed to escape in his slippers. He ran to warn his wife, but she had already been arrested three hours before him. He then hid in Smíchov, with friends from the evangelical congregation of which they were both members. He eventually escaped, learning about his wife’s execution in a refugee camp. He did not see his daughter for the first time until seventeen years later when she was allowed to join him in the USA, and then in 1968, when she moved in with him permanently.

Jana Kánská, Milada Horáková’s only daughter, when talking about the opera Zítra se bude… (Tomorrow Will Be…): “I accepted that there would be an opera, which I didn’t have much faith in at first, because I thought: oh my God, this is something unusual. And suddenly I began to realize that of all that has been done here about my mother, this is the most beautiful, spiritual, and pious thing that will appeal to people for a long time.”

The opera Tomorrow Will Be… was created with the intention of being staged at least six times. In the end, it ran for more than five years, with the number of performances stopping at 85.

Job Satisfaction

Soňa Červená was completely devoted to the theater: “I didn’t go to restaurants because people smoked there. I didn’t go on binges. It was a monastery. But a beautiful monastery. The stage gave me strength for everything else. And that’s why I rejected everything else. I didn’t start a family, a household. I stayed single, and from that solitude I renewed my strength.”

However, that doesn’t mean she went through life alone. She had many friends, and a lifelong love for thirty years. SČ: “I often asked myself what turn my life would have taken if I had decided to follow him into the world. But what good would a wedding ring have been to me, which I would have take off before every performance anyway? I was happily married to my profession.”

We agreed that we would not leave our jobs, but it felt like eternity whenever we would meet. It lasted thirty years. In between, we wrote to each other. Hundreds and hundreds of letters. When we were both in Europe, we called each other every day. For thirty years. I loved our calls. The mere ringing of the phone seemed to sound softer when it was his. Of course, we couldn’t call other continents every day. Sometimes we agreed to call each other at a certain time, so that we could at least hear the phone ring. But we usually couldn’t resist picking up the phone. He was wonderful. The only thing he shouldn’t have done to me was die. That brought my world to pieces. But life went on.”

Thoughts and Quotes

The main thing is not to look back, not to remember and not to regret. It only matters to have a clear conscience and try to keep a good track. / I wouldn’t be happy if I was only half or three-quarters ready. I always have to be 130 percent ready. That’s my life, that’s me. / Talent is essential, but it’s 50%. And 50% is obsession, diligence and humility. / What’s important about a voice is its color. No one can give you that. / I think that growing old and dying is the greatest justice in the world. Even though it’s sad. I don’t want to leave this world. I know I’ll have to, but as I say: there’s no rush. / It’s really stupid to fall for your perfection, you can’t do that. At least I always doubted myself. And those doubts brought me even higher. / When a journalist asked her how she dared to go on set without a script at such an advanced age, she smiled at him and said: “Well, you have to learn that, little boy.” / You can’t be betrayed by something you give everything to. Even yourself, your diligence, and work. You don’t cheat on anything in life. Not love, not art. Nothing.

Epilogue

Soňa Červená lived for decades outside her country, hidden behind the Iron Curtain. She loved it as much as she loved art. Her foundation is the result of these two loves: “Now, at the end of my life, I have decided to start my own foundation. Because despite all the blows, fate has directed me as best it could, gifted me – and now I have decided to share all the gifts. The Soňa Červená Endowment Fund is my gift – FOR CZECH CULTURE AND EDUCATION.”

Her last opera role was the Countess in Tchaikovsky’s The Queen of Spades at the Mahen Theater in Brno in the spring of 2022, her last melodramatic role was the character of Saint Ludmila in Jan Zástěra’s oratorio A Breath of Eternity, last performed in Italian in the Lateran Basilica in Rome on September 29, 2022. Soňa Červená was 97 years old at the time.

When she was dying, she had no strength to speak for the last two weeks. Her friend was taking care of her in the hospital. When she saw that she was trying to move her lips, she leaned her ear to her lips and heard: “The Czech land, my home”, which is the last verse of the Czech anthem…

Wedding photos of František and Soňa

Soňa Červená and Jana Kánská, daughter of Milada Horáková

Soňa Červená, director Robert Wilson and one of his painted letters

2x Soňa Červená

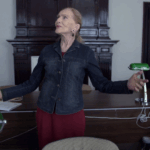

Olga Sommerová and Soňa Červená in the research room of the Security Forces Archive, Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes. The research room is on Na Struze Street. In the SAME apartment where Soňa Červená grew up. The living room is the research room, Žofia Veselíková’s bedroom is the director’s office, and Soňa Červená’s former room is the office of the head of one of the institute’s departments. SČ: “It’s interesting that in this apartment where I grew up, there are secret police documents against our entire family.”

Olga Sommerová holding an honor guard at the coffin of Soňa Červená on the stage of the National Theater / Director Olga Sommerová – the last farewell to the opera singer Soňa Červená

Farewell to Soňa Červená in the church in Hradec Králové

Soňa Červená left nothing to chance. That’s why she also thought about where she wanted to be buried. First, she considered the grave where her mother is buried in Vyšehrad. But then she decided on a tomb in her beloved Hradec Králové, where her great-grandfather’s factory was and where, in addition to her father, great-grandfather, and great-grandmother, other of her ancestors are buried. So she had a black tombstone made “in time” with her golden signature and was personally present at its installation on the grave.

When you are young, a smile is all you need. When you are old, you should try to smile from within, to be at ease, to be kind. (Until April 9, 2026, there is an exhibition about Soňa Červená with this opening quote in the Museum of Music, within sight of the Infant Jesus of Prague.)

On June 22, 2018, Soňa Červená received a certificate that a planet had been named after her. The planet number 26897, which is in the sky in the orbit between Mars and Jupiter, was named Červená. Soňa Červená was thrilled by the honor: “I always wanted to leave a mark here, but this is truly amazing. This is a mark forever! I will always look at you. All of you.”

On the exact day of her 100th birthday, a bust of Soňa Červená was unveiled at the State Opera, which, along with the historic building and the Estates Theatre, is one of the stages of the National Theatre.

Until May 2026, there is an e-exhibition about Soňa Červená on the website of the National Theater Brno

In Prague’s Kampa, the narrowest and shortest streets in Prague are just a few hundred meters apart. The narrowest one is besieged by tourists, the shortest one is known only to locals. It is named after Jiří Červený, the father of Soňa Červená. She pushed for the renaming of the previously nameless street in cooperation with the then Minister of Culture, Pavel Dostál, who was a theater person at heart and soul, so he was happy to oblige. She thus fulfilled the wishes of her father, who wrote a poem about the renaming of the street.

The text uses quotes from Sonia Červená from both of her books and from Olga Sommerová’s documentary

You can rent or buy the documentary Červená here