Loreto Square is bordered by the Capuchin Monastery on the northern side, the Czernin Palace and its garden on the western side, the Loreto (a monastery and pilgrimage destination) on the eastern side and the House at Drahomíra’s Column on the southern side. It is an oblong space paved with the classic cobblestone pavement called in Czech “cat heads,” nowadays very idyllic and romantic.

However, this was not always the case. There used to be a terrain break in those places, then a muddy dirt ravine road. The area was inhabited as early as the 9th century, and from the 10th century there could be found the oldest burial ground in Prague. During archaeological work in the 1930s, 592 skeletal graves from the Middle Ages and early modern times were discovered. In the 16th century, the remains of people who died a violent death were also buried here.

Loreto Square was not only a burial ground but also a place of execution. And not just any execution ground – the local execution ground was intended for the execution of people of the nobility, while “common” criminals were to be executed further beyond Pohořelec.

The Loreto execution site is Europe’s largest known burial site for the executed – many graves were found here where a severed skull is placed next to the skeleton. It is certainly interesting that execution by sword or ax was considered a privilege that was not granted to everyone sentenced to death.

And what stories might we be able to share?

In 1512, two robber knights, the Chlevec brothers, were executed here. A contemporary commentary says: “They took them to the place of execution in Hradčany, where the executioner impaled both of them on stakes and raised them high. One of them soon lost his soul, but the other was still alive during the night, and when the stake broke with him, he dragged himself to the nearby church of St. Benedict where the priest administered the sacrament to him in the morning, and only then did the murderer die.”

In 1537, on Loreto Square, the executioner beheaded Jaroslav Kapoun from Svojkov and Mr. Vlkovský from Vlkov, who falsified a last will and testament. In 1544, Burian Medek from Valeček, who committed false testimony, received the same punishment.

The story of Kašpar Rucký from Rudz, the butler of King Rudolf II, is a bit more intense. Kašpar was arrested on the day of the king’s death and accused of political intrigue and robbing the king. He was imprisoned in the White Tower, where they threatened to torture him. Kašpar could not stand this psychological pressure and hanged himself on the silk cord he used to carry the key to the castle chambers on.

Even after his death, however, Kašpar was not treated too kindly. The executioner threw the corpse from the window of the White Tower, loaded it on a cart, and drove it to the execution ground. He cut off the body’s arms and legs, ripped out the heart, and slapped the dead man’s face with it. Then he cut the body into pieces and threw it into the grave. However, after the rumor soon appeared that the ghost of Kašpar Rucký was haunting the castle, the executioner dug up the dismembered body and burned it.

The executions were not always dangerous only for the convicts. We have documented at least two such stories. In 1509, the executioner beheaded two convicts. The first execution was carried out properly, but in the second, the executioner’s work was unsuccessful, so his assistant had to “finish the chopping.” The onlookers were so outraged that they first shouted at the two executioners and then stoned them.

In 1588, a man who killed a Jew in an argument in the Jewish Quarter was to be executed in Loreto Square. The executioner was so clumsy that the head did not separate from the body even after the third hit with the sword. This angered the onlookers so much that they attacked the executioner and his assistants and stoned two of them to death.

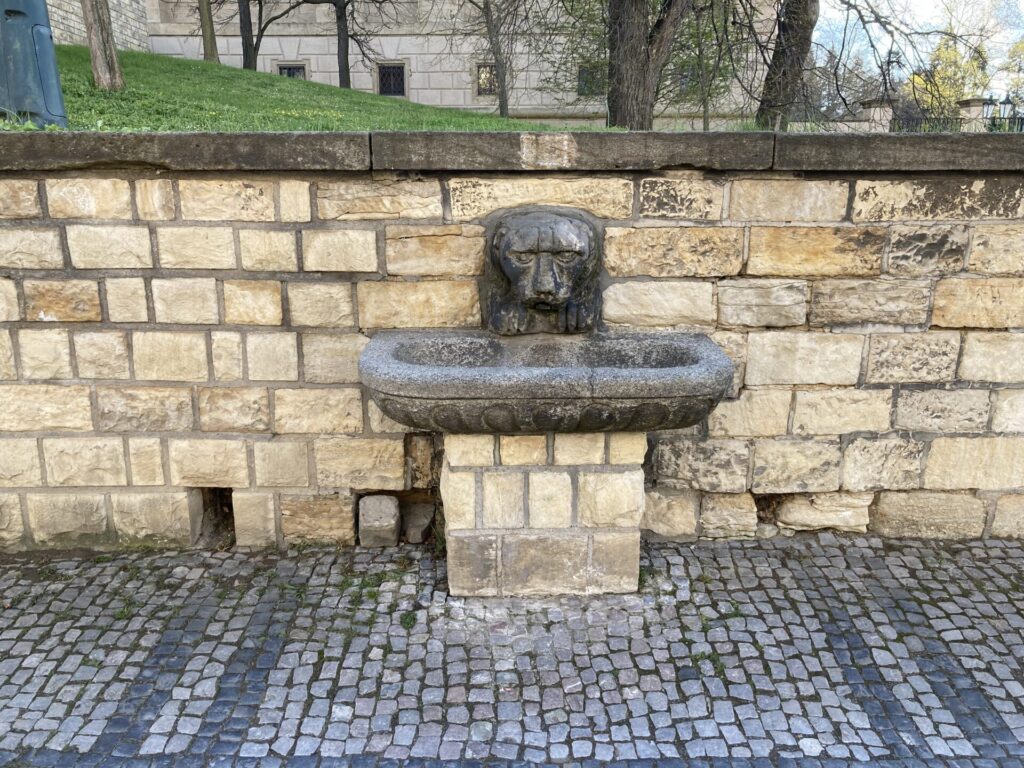

You won’t see any of this wild history in Loreto Square anymore. All the tangible evidence has been taken away over the years. With one exception. At the beginning of the terrace in front of the Czernin Palace building (the seat of the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs) stands a statue of President Edvard Beneš. If you walk around it and down to the terrace wall, you will discover large stones in the wall. And these are the direct participants of ancient history…

The oldest finds from the burial site on Loreto Square date back to January 1902, when a woman’s skeleton was found in a crouched position and covered with a red sandstone slab, supported by larger stones, during excavation for a new water supply.

From this investigation, and especially from the extensive archaeological work in the 1930s, we know that the arrangement of the graves on Loreto Square soon changed from terraced to staged – up to ten levels of graves were discovered, stacked one above the other. Some graves were lined with marl stones; many were also placed with massive sandstone tombstones.

Several of them, dating from the 11th to 13th centuries, are embedded in the terrace wall. The stones are freely accessible. If you touch them, for a moment, you will be connected to the ancient history of this place. Once so cruel, now infinitely calm and romantic.

By the way – if you really want to experience the local genius loci, you can spend the night in the Capuchin Monastery. You can order accommodation here.

Using information from the work of Ivana Boháčová and Gabriela Blažková: Pohřebiště na Loretánském náměstí v Praze – Hradčanech (in English, title translated as: Burial Grounds at Loreto Square)