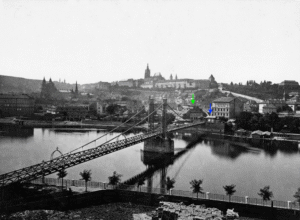

If you look at Vyšehrad from the river, you can see two church towers and a massive wall. The walls were built in the middle of the 17th century when it became clear that the original medieval fortifications were unable to withstand new weapons, cannons. The entire Vyšehrad complex was thus turned into a fortress at the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries.

As Prague developed, the significance of the walls on the city’s borders became less important. When the Masaryk Station, the first station in the middle of the city, was established in 1845, gates had to be set up in the walls for trains to enter the city – these were closed at night with bars. In 1860 it was decided to demolition the walls – however, parts of them can still be seen in many places in Prague today.

Vyšehrad Fortress is one of the most visited places in Prague today – although not much was missing for it not to be there at all. At the beginning of the 20th century, it was thought that the fortress would be demolished to make way for the construction of houses. This would have been a repeat of the situation during the construction of the Vyšehrad fortification when many houses were demolished and their inhabitants had to move elsewhere. At that time, it was such a big intervention into the city’s layout that only the redevelopment of Josefov was bigger.

One of the people who opposed the demolition of the Vyšehrad fortifications was the architect Josef Chochol: “It is a mistake to think of Vyšehrad only as a fortified hill, a military fortress that does not serve the city. With the demolition of the walls, the ramparts supported by them will fall, the height of the hills will decrease considerably, the gentle slopes will draw the already low hill even more into the flat terrain and, with the exception of the rock above the Vltava, the impression of massiveness and strength will disappear. By tearing down the walls and ramparts, everything will merge and Vyšehrad will disappear from the horizon of the city. ”

Fortunately, the walls of Vyšehrad were not demolished and a few years later Josef Chochol built several houses under Vyšehrad, which are now considered to be jewels of Cubism.

Czech Cubism in architecture is unique in the world – nowhere in the world is there such a large number of cubist buildings as in our country. The most famous Cubist buildings in Prague are the House of the Black Mother of God in Celetná Street, Kovařovic’s villa on the embankment below Vyšehrad, and the cubist three-house there. Apart from these, it is also a tenement house in nearby Neklanova Street, the Libeň Bridge, and the Diamant House in Lazarská Street. (A unique cubist monument is also the lamp on Jungmann Square.)

The Kovařovic Villa was built in 1912-1913 by Bedřich Kovařovic according to the design of architect Josef Chochol. It was built on the site of the former Schwarzenberg brickyard.

In 1944, the building was extensively rebuilt, leaving almost nothing of the cubism in the interior. Between 1960 and 1995 it was a kindergarten, but then the villa underwent extensive reconstruction under the supervision of architects. The original windows, doors, fences, and cubist garden plan were restored.

Closer to the Vyšehrad Tunnel stands another famous building by Josef Chochol – a Cubist three-house, built by three important families of architects. Each of them owned one part of the house, which was separated from the other and always had a small garden on the other side of the house.

In the middle house lived for many years the popular Czech actress Marie Rosůlková with her brother Jan, a priest. She died at the age of 92. She was known for her unmistakable humor. Her sentence about the legend of Horymír and Šemík is known: “To those who do not believe that Horymír jumped from the Vyšehrad rock with his Šemík, I can only say, I saw it with my own eyes!”

You can see her apartment and garden in Dagmar Hájková’s photos.