At the beginning of Prague’s existence, the left bank of the Vltava River was more populated. One of the many reasons was that the right bank lies on a plain, so floods threatened it more. It is easy to see this – take a walk on the Charles Bridge. In Lesser Town, Nerudova Street rises steeply, and when you reach the Prague Castle, you’ve suddenly climbed 60 meters and even more than 70 meters on Pohořelec. However, you’re still walking level on the Old Town side of the bridge. And even if you walked from the Old Town Square to the end of Karlín, where you would walk for 45 minutes, you would not go uphill or downhill anywhere. We are not mentioning Karlín by chance – it is a special district that has blossomed into a real gem in recent years like no other district in Prague. And paradoxically, it was precisely the flood that sparked this.

The first mention of the territory of today’s Karlín dates back to 993, when Prince Boleslav II donated the local land to monks from the Benedictine order. They turned it into fields and grew vegetables and fruits. Despite this, Karlín wasn’t permanently settled until several hundred years after other parts of Prague, mainly due to the regular floods. This is because Karlín is on a floodplain of the Vltava – i.e., an area formed by river deposits and regularly inundated and shaped by floods. One of the biggest affected the territory of present-day Karlín in the 15th century – if the Hussite wars didn’t destroy it, the flood did. It wasn’t much better in the following centuries either – just between 1768 and 1893, ample water flooded the territory of Karlín a total of seven times.

Karlín began to be more systematically settled in the 19th century; it became a part of Prague only in 1922. And because it was built “on the greenfield” and the new development did not follow the medieval buildings, Karlín has a unique character – long straight streets that look like the architect would simply draw them on the map with a ruler. Karlín’s main artery, Křižíkova Street, is more than one kilometer long, and you can see from one end to the other.

This street is an imaginary connection between two significant military buildings. Karlín Barracks and Invalidovna (the House of Invalids). And this is a fascinating building worth seeing (you can get there by metro from Můstek on the yellow line B in 6 minutes, information for visitors).

The Invalidovna was built based off the model of the Paris Les Invalides, i.e., a home for old or disabled war veterans. It was designed by Kilian Ignác Dientzenhofer, probably the greatest Czech Baroque architect, as his largest secular building. Initially, a complex consisting of nine squares of autonomous buildings was to be built – in the end, a single square of buildings was built, nevertheless monumental and respectable.

The story of the Invalidovna began in 1657 when Count Petr Strozzi was seriously wounded in battle. Believing that he would die, he wrote a will that mandated the creation of a foundation for the care of wounded and aged soldiers and officers – on the condition that he would die childless and his wife did not remarry. He eventually recovered but died a few years later at age 38, ironically killed by a stray bullet during a parade after a victorious battle. Countess Marie Kateřina Strozzi died in 1714, and her husband’s will came into force with her death.

The Invalid House included a hospital with a pharmacy, a canteen, shops, workshops, the Chapel of the Holy Cross, a two-class school for children of soldiers, but also a prison, a morgue, and a cemetery. The extensive grounds around Invalidovna were military training grounds, warehouses, and shooting ranges. We find the most people staying here in 1854- 1,400 war veterans.

War invalids stayed in quarters that were separated from each other by a kitchen and a storeroom. 32 – 35 soldiers lived in one quarter, and non-commissioned officers or war invalids and their families lived in apartments on the gallery. Senior officers had much more luxurious accommodation on the first and second floors of the north wing of the building, including a particular room for servants.

The soldiers and their families had to follow the daily schedule with the usual military regime, i.e., wake-up call, lights-out, and permission to go outside the campus. The Invalidovna was built as a separate residence behind the walls of the city’s fortifications. Over time, however, as it grew, Prague absorbed it and the Invalidovna building thus became a kind of “city within a city.” It served its original purpose until 1935, when many military organizations, such as the Military Archive, were based here.

The saddest day in the modern history of the Invalidovna came on August 15, 2002, exactly on the 270th anniversary of laying its foundation stone. At that time, Prague was hit by a flood that inundated a large part of the city with Karlín hit the hardest. The water in the streets rose to more than 3 meters, flooded many metro stations, and rescuers rode in boats on the roads of Karlín.

The Invalidovna was flooded – many documents of the Military Archive were irretrievably destroyed, and thousands of boxes of documents were frozen and gradually restored. The Invalidovna has been partially repaired, but the effects of the flood are still visible in many parts of the building.

The future purpose of this baroque complex of buildings has not yet been decided; however, for Karlín, the flood was paradoxically a change for the better. Living in Karlín certainly did not mean having a prestigious address. On the contrary, after the flood, Karlín turned from a gray and neglected factory district into one of the city’s business centers. With almost 400,000 square meters of office space, the vast majority of which was created after the flood, Karlín is the third largest office area in Prague. Of the companies that settled here after the flood, 25% are in the information technology sector, 16% are in consulting, auditing, and law, and the same number of companies are banks, insurance companies, and other financial institutions.

This rapid development of Karlín is, of course, matched by the number of cafés and bars. So if you go to see Invalidovna, you’d better walk back to the center. On Křižíkova Street and on the side streets, you will have many options: sit down, have a coffee or something good to eat, and enjoy this district for which the flood was a gift from heaven. Or actually – from the river…

Many movies were filmed in the Invalidovna buildings. Historical movies, but also fairy tales and fantasy stories. Miloš Forman was one of the first to shoot the film Amadeus here, which later won 8 Oscars. The Invalidovna was then a hospital for the mentally ill, where Mozart’s rival Antonio Salieri was placed at the end of his life.

The most famous resident of the Invalidovna was Josef Sudek, who was hit by a grenade on the Italian front in the First World War as a twenty-year-old, and doctors had to amputate his right arm. He lived in Invalidovna from 1922 to 1927, trained as a photographer, and became one of the most famous Czech photographers. In his honor, the park in front of Invalidovna is called Sudek’s Gardens.

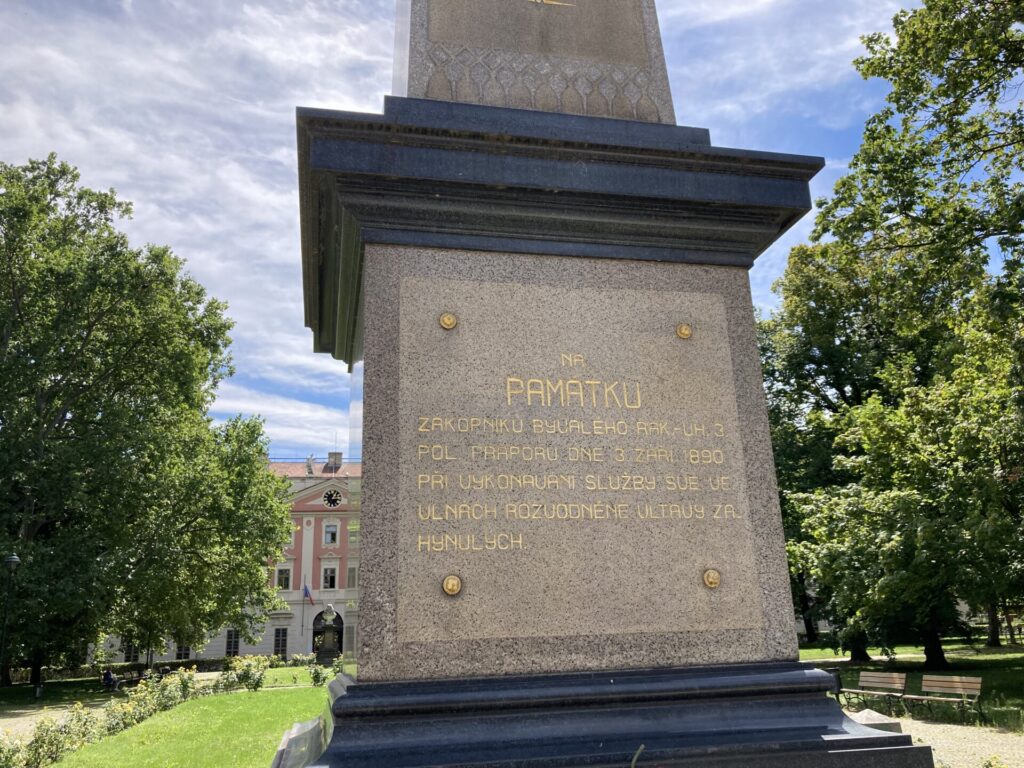

In this park, a monument commemorates the memory of the sappers who were at the Invalidovna for military training in 1890. At that time, Prague was hit by a flood, which only flooded the Invalidovna to a height of 40 cm, but caused more damage elsewhere in the city. Twenty soldiers were called to fight the elements, but unfortunately, they drowned on the broken pontoon bridge.

Thanks for the tour and the information provided by Mrs. Tereza Antošová, National Heritage Institute.