The doorbell rang. The man carefully opened the door and when he saw the police standing in the hallway of the house, he whispered: “What do you want?”. One of the policemen also whispered: “Police!”.

“Here’s the theatre performance. Come in, but be quiet.”, he told the policemen and entered the kitchen with them. They all then waited for the end of the performance.

The man was a movie cameraman Stanislav Milota. The apartment belonged to him and his wife, actress Vlasta Chramostová. And she was the protagonist of the ongoing theatre performance.

The incident is comical. And it very well documents the ridiculousness of the socialist regime in the way my generation knew it.

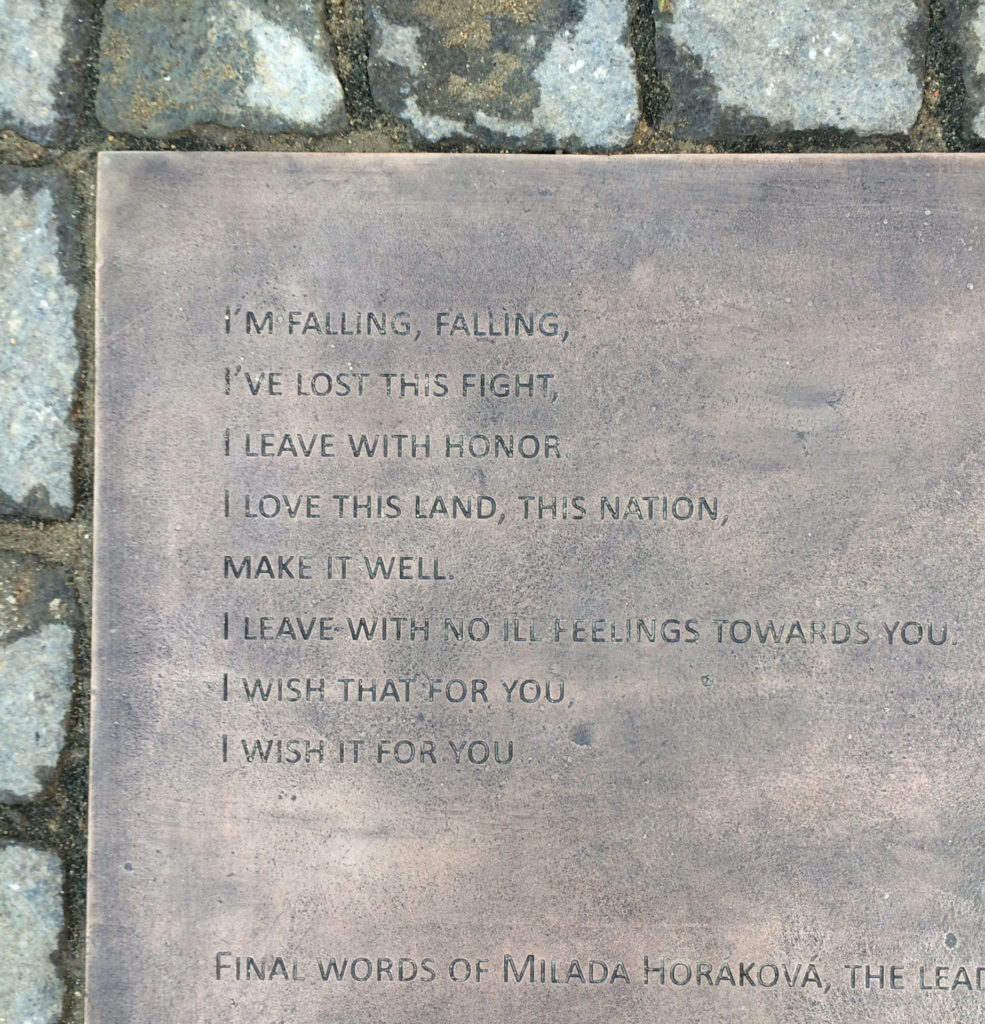

We did not experience the brutal 1950s, when enemies of the socialist regime were sentenced to death, such as the Czech politician Dr. Milada Horáková. At that time, hundreds of thousands of people were sentenced to prison, hundreds of people were executed, and thousands died in prison as a result of cruel treatment.

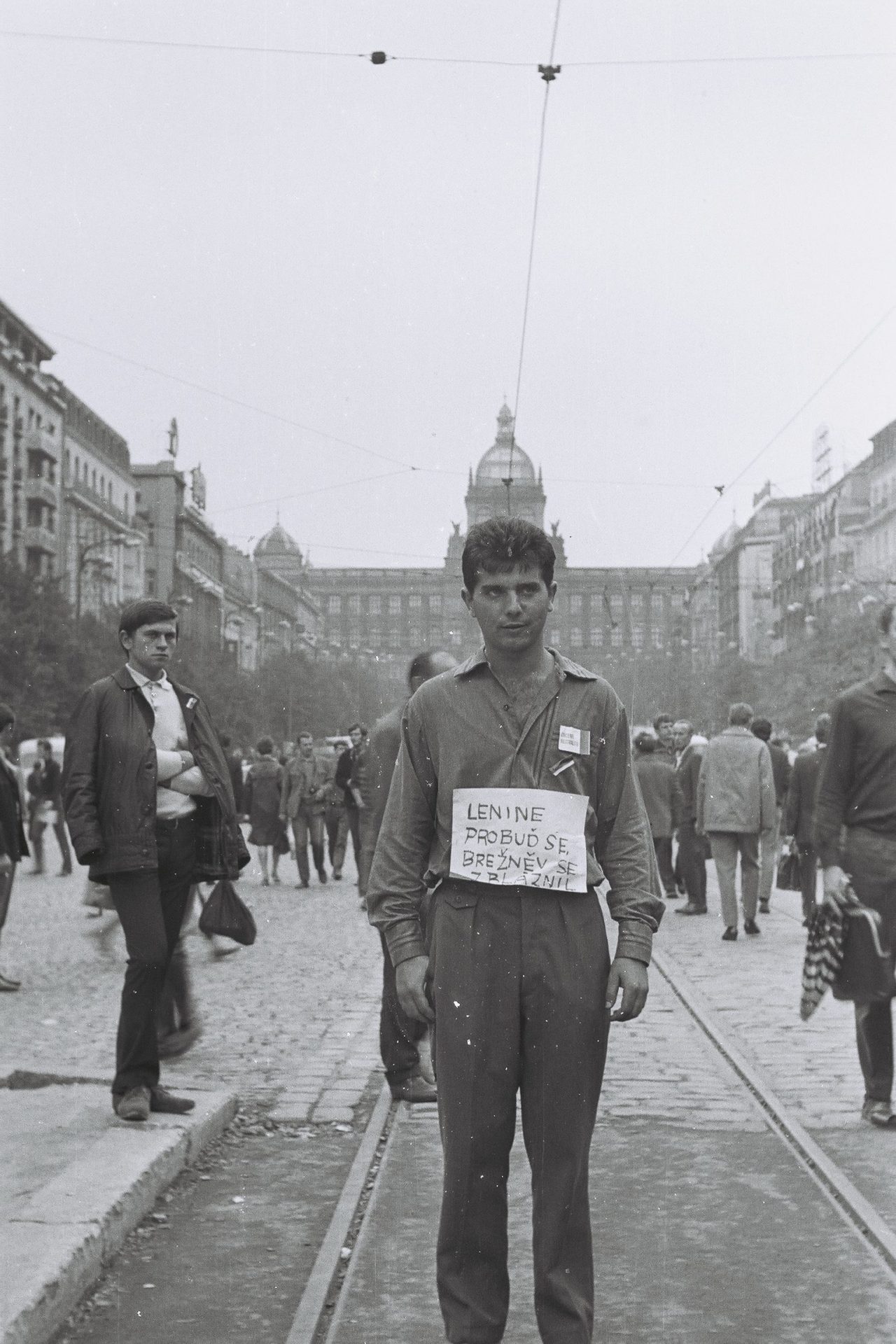

But then, during the summer vacation after the first grade of elementary school, we experienced an occupation on August 21, 1968, when we were occupied by the Eastern Bloc armies led by the Soviet Union. These are memories that no one can erase from your memory, even if you have experienced them as a small child.

The 1970s in Czechoslovakia are called the period of normalization, although nothing at all was normal at this time. In January 1977, Václav Havel and his friends issued a declaration of a new citizens’ initiative, Charter 77. In particular, they criticized the state for violating human and civil rights, something the state committed itself to at the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe held in Helsinki in August 1975. Further repression followed, especially against the signatories of Charter 77, but also against the people who read it, although there was nothing in the text to disagree with. All of this only strengthened our opinion that the socialist regime is ridiculous and deserves nothing but contempt.

Protests began in January 1989, the 20th anniversary of the burning of Jan Palach. (A student of the Faculty of Arts of Charles University, who burned himself on 16 January 1969 in protest against the “Russian occupation” of August 1968.) The protests continued for five days, totalitarian police intervening against them using batons, waterworks, and tear gas. 1 400 people were detained, Václav Havel was arrested and imprisoned in March 1989. In June 1989, Charter 77 issued a petition called Several Sentences with demands for a totalitarian government. With demands that we take for granted today (for example, the release of political prisoners or the guarantee of assembly rights). The petition Several sentences could not be downplayed by the regime – also because it was signed by many personalities of Czech culture. It was obvious that the regime was more and more a titan standing on clay feet.

The protests on August 21, 1989 were less massive than the regime had anticipated and were preparing measures against. It was evident that the regime was more afraid of its citizens than the citizens were of it. The fall of 1989 marked the collapse of the Eastern bloc totalitarian regimes.

In the Czech Republic, the collapse happened on November 17, 1989. The students wanted to commemorate the student Jan Opletal, who was killed by the Nazis in October 1939 (His death caused a wave of student protests. As a result, 1200 students were then sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp and nine student leaders were executed on November 17, 1939). Since then, November 17 has been declared International Student Day. The police surrounded the student protest on Národní třída and beat them up. Almost 600 people were injured, many of them very badly. The Velvet Revolution began, our first step towards regaining democracy. And I would like to bring it for you closer to it through the fate of three people who played a big part in it.

Vlasta Chramostová, actress

Every totalitarian regime proceeds in the same way. When the leader comes to power, he first wipes out those opponents he knows he could never intimidate. He organizes staged trials and then either sentences his opponents to death or places them in jail, or expels them out of the country. This will consolidate his power and then the regime just bullies people, using the “sugar and whip” method. The regime rewards obedient citizens and punishes the disobedient. It also punishes “nameless” citizens, but above all it punishes those who are known because their resistance is more effective. That was the story of actress Vlasta Chramostová…

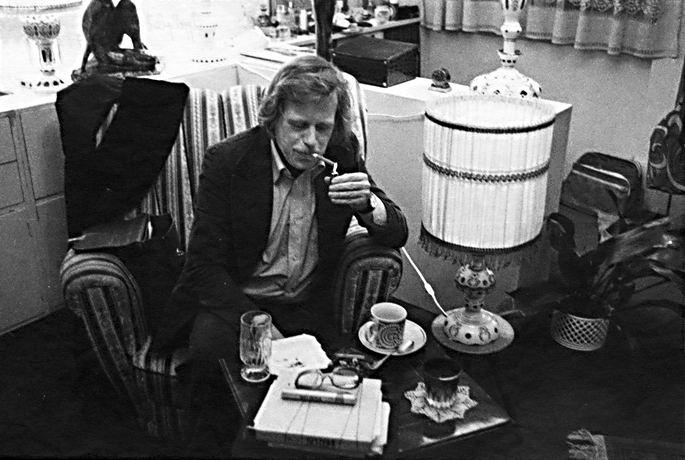

Vlasta Chramostová was one of the best Czech actresses who performed in the best Czech theatres. Her husband was cameraman Stanislav Milota, who during the Russian occupation of 1968, filmed a lot of documentary footage. In January 1969, he also filmed the funeral of Jan Palach.

Because of their political attitudes, they were both gradually deprived of their work. After 1968, Vlasta Chramostová was not allowed to work in film, television or radio. She had to leave the theatre where she was still playing, and later was only allowed to play in the theatre outside of Prague. In 1977, they both signed Charter 77 and as a result, were not allowed to work at all.

I know, it’s incomprehensible to a person who has never lived under a repressive regime. But when television, radio, and all film productions are state-owned, it’s easy to ban the work of a nonconformist artist, while also warning others. A better example would be: try to imagine that the state would tell Diane Keaton that she must never make a movie again. It’s a crazy idea, isn’t it? As crazy as everything in an unfree country.

A totalitarian regime may forbid an artist from working, but it cannot destroy his relationship to art. Vlasta Chramostová was not allowed on the Czech stages, so she created a stage in her home – and the project called Housing Theatre was created. She played for friends, mostly in her home, but also at the cottage of the later Czech President Václav Havel.

The Velvet Revolution took place on Vlasta Chramostová’s 63rd birthday (born November 17, 1926). For her, it was a gift of civic and artistic satisfaction. She was engaged in the National Theater, where she performed in lead roles until the age of 84. President Havel awarded her the Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk Order for Merit in Democracy and Human Rights. When she died in the fall of this year at 92, she had a funeral with state honors at the National Theatre. Justice has prevailed.

Jan Potměšil, actor

Jan Potměšil was a successful children’s actor. He graduated from the Theatre Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts, performed on television and in movies, and also at the famous Czech theatres. He was an athlete as well as one of the leading acting idols, his posters hanging on the walls of many girls’ rooms. In the fall of 1989, Jan completed his studies at the theatre faculty and immediately got an assignment at the Vinohrady Theatre – the same prestigious theatre from which Vlasta Chramostová was thrown out of years before.

If we wanted to compare it – in 1989, Jan Potměšil was 23 years old and could be described as the Czech Brad Pitt.

In 1989, it was important that news of the massacre of students in Prague spread as quickly as possible across the country. And because television and newspapers were state-owned and nothing could be learned in the first few days, actors, directors, and theatre students began to travel across the country telling people what was happening in Prague. This was absolutely essential because without the support of people outside of Prague there was a risk that the Communists could stifle the revolution.

When one such informant was driving at night from industrial Ostrava, whose support was very important, the driver fell asleep behind the wheel and his car veered off the highway. Jan was thrown from his car and it rolled on top of him. It didn’t crush him only because he was laying in a pit. He was paralyzed from the waist down and fell into a coma for three months. When he woke up, his dad told him that Václav Havel was already president.

Two years after the accident, theatre producer and director Jakub Špalek came to Jan and told him he didn’t care that Jan could not walk and instead praised his acting and talent. Since then Jan performs theatre and is one of the best Czech theatre actors. He got married and now has a son. He is happy that we have a democracy and says: “I don’t regret anything. A wheelchair is better than communists.”

The audience does not perceive Jan`s wheelchair on stage. One spectator even told him at the theater club, “Did you come here in the wheelchair?” He thought it was just a prop.

Marta Kubišová, singer

Until 1970, Marta Kubišová was one of our best singers. Apparently that’s why the regime chose her, to show that it could do anything, like forbidding singing to a popular star. It happened after a scandal with fake porno photos. Everyone knew it was a lie and Marta Kubišová proved it in court, where she won. However, her career was stopped.

In 1977, when she signed Charter 77 and even became spokesperson, it was clear that the regime would never allow her to sing. (In comparison, it would be a similar situation if the state would forbid singing to Barbra Streisand. I know it’s absurd. But the totalitarian regime is absurd at the core.)

One of Marta Kubišová’s most famous songs was Prayer for Marta:

Let peace remain with this country

Malice, envy, spite, fear, and strife

Let those pass, let them finally pass

Now that your lost governance of your affairs

Is returning to you, people, is returning

The cloud is slowly flowing away from the sky

And everyone is reaping what they’ve sown.

My prayer, let it speak

To the hearts which, by the time of ire,

Were not burnt, like flowers by frost, like by frost.

Let peace remain with this country.

Malice, envy, spite, fear and strife,

Let those pass, let them finally pass

Now that your lost governance of your affairs

Is returning to you, people, is returning.

We all knew the song and we all loved it – at a time when we knew that the singer had inferior professions in order to make a living. It was when, to everyone’s great satisfaction, Marta Kubišová sang Prayer for Marta during a large demonstration on Wenceslas Square in November 1989, that reinforced our belief that we will succeed in the revolution. Marta Kubišová herself said that this memory in her mind could never be overcome. Her artistic revenge towards the regime came a few days later, when she sang the Czechoslovak anthem to the grand gathering at Letna.

Prayer for Marta became the second Czech anthem and it is always played when it is necessary to fight again for the ideals of freedom and democracy.

And Marta Kubišová? She sings, performs theatre, and takes care of abandoned dogs. She is the person with the highest moral credit. The nation loves her.